The short winter afternoon was drawing to a close, and a grey mist had already begun to blot out the canal and the trees which were studded along its banks, accentuating the prevailing cheerlessness and silence, and throwing into yet stronger relief the animated scene presented within the comfortable, well-warmed dining-room of a house standing on the further side of the broad street which ran parallel with the canal. A large company was gathered in this room for the enjoyment of music and conversation, and it was evident from the whispered remarks which passed between the guests that something out of the common was expected at the hands of the youthful player who, in obedience to his father's request, now advanced to take his place at the pianoforte.

Peculiarly winning, both in manner and appearance, was the boy who modestly seated himself at the instrument. He was about thirteen years of age, of slight build, with a handsome face, in which strong traces of Jewish descent were apparent. His black hair clustered thickly above a high forehead, while the dark, lustrous eyes, with their continuous play of expression, imparted to the face an indescribable charm such as no degree of beauty in itself could have exercised. It was, in a word, the sensitive face of an artist, reflecting the varying imagery of a mind attuned to lofty and beautiful thoughts; and as such its power and charm could be felt even by those to whom as yet his thoughts were a sealed book. The temperament which we designate by the term 'artistic' resembles the ocean in its varying moods, and in the surprising swiftness with which one mood or aspect gives place to another. Just before he was called upon to play, the boy's eyes had been sparkling with merriment, and his spirits had so infected the rest of the company as to cause the intervals separating the performances to be filled with laughter and merry chatter. Yet no one watching his face now, as his fingers swept over the keys, could have failed to be struck by the change in its expression. Every trace of fun had vanished, and to the sparkle of the eyes had succeeded an expression of deep earnestness that showed how readily the mind had adapted itself to the character of the music he was playing, and as the performance progressed one could have read in his face every shade of feeling which the music was intended to express. No self-consciousness marred the spontaneity of the player's interpretation. Everything seemed to come direct from his soul, as if that soul had found the voice by which alone it could be heard and understood, and revelled in its freedom. And as he played on, weaving fresh melodies out of the original theme, ever and anon breaking through the web of harmony to recall the simple, plaintive air with which he had begun—his face at one moment lighted up with radiant happiness and at the next shaded with quiet sadness—his listeners almost held their breath, fearful of losing any portion of the music which was passing away from them, perhaps for ever. And as he played, the shadows of the December afternoon crept into the room, enveloping the slight figure seated at the instrument, until his outline became lost to view, and the melody pouring forth from beneath his fingers seemed to come from heaven itself.

To those who visited the home of Abraham Mendelssohn, the wealthy Berlin banker, the fact that his son Felix had a remarkable genius for music did not admit of a doubt. The capacity for learning music had begun very early, but his wonderful gift of extemporisation, which gave his genius wings as well as voice, had only lately revealed itself at the time at which our story opens. Nevertheless, it had made great strides, and opened up all sorts of possibilities with regard to the future. And withal there was such an unaffected modesty and simplicity about the boy, so complete an absence of anything like a desire to show off his talents, as sufficed to disarm any tendency towards captiousness on the part of his hearers. Felix's whole wish was to satisfy himself as to his progress in music, and, young as he was, he had the sense and determination to pursue his bent without regard to the plaudits of his father's friends. Abraham Mendelssohn, notwithstanding his business capacities, was himself a great lover of the arts, and especially of music, in regard to which, indeed, he showed considerable judgment. That his children should exhibit similar tastes to his own was, therefore, to him a matter of delightful satisfaction, for he shared with his wife Leah a deep interest in all that affected his children's education. He watched Felix with peculiar care, for it seemed to him that he inherited many of the traits as well as the capacity for learning which had distinguished the grandfather and philosopher, Moses Mendelssohn. Felix undoubtedly possessed the bright dark eyes and the humorous temperament of his grandfather, for he was one of the brightest and merriest of children. The family was not a large one. Jakob Ludwig Felix (to give the subject of our story his full names), who was born February 3, 1809, ranked second in age, the eldest child being Fanny Cäcilie; after Felix came Rebekka, and, lastly, little Paul. The three elder children were born in Hamburg, where the family continued to reside until the occupation of the town by the French soldiers in 1811 made life there so miserable for the German inhabitants that as many families as could contrive to do so escaped to other towns of Germany which were free from the presence of the invading army. Amongst those who successfully eluded the watchfulness of the French guards by resorting to disguise was the family of Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, the head of which had followed the example of his wife's brother in adopting the latter name as a means of distinguishing his own from other branches of the Mendelssohn family. With his wife and children Abraham fled to Berlin to make his home in the house of the grandmother, situated beside the canal in the north-east quarter of the town, to which we have been already introduced.

No happier surroundings could have been imagined than those amidst which Felix Mendelssohn's childhood was passed. The residence was in the Neue Promenade, a broad, open street, bounded on one side only by houses, and extending on the other side to the banks of the canal. Here a wide stretch of grass-land, with a plentiful dotting of trees, imparted a pleasant suggestion of the country, whilst the waters of the canal reflected the blueness of the sky, or, when rippled by the breeze, lapped the grassy banks with a murmuring sound that was half sigh, half song. To this spot daily resorted the Mendelssohn children in company with the occupants of other nurseries in the promenade, and here amongst the rest might often have been seen little Felix, his eyes sparkling with merriment, and his black curls tossed by the wind, as, with surprising quickness of movement and ringing peals of laughter, he joined with his sister Fanny in the excitement of the game.

Every encouragement was given to the development of Felix's musical talent as soon as his fondness for the art made itself apparent. In company with Fanny he began to receive little lessons on the pianoforte from his mother when he was about four years old. Then came a visit to Paris, when Abraham Mendelssohn, taking the two children with him, placed them under the care of a teacher named Madame Bigot. Their progress was so satisfactory—for the lady was an excellent musician and quick to recognise the abilities of her pupils—that on their return to Berlin it was decided to engage the services of professional musicians to carry on the instruction in the pianoforte, violin, and composition as a regular part of the children's education. There was a continual round of lessons in the Mendelssohn home at this time, for in addition to music the children were taught Greek, Latin, drawing, and other subjects; and with so much to get through it was necessary to begin the day's work at five o'clock. As a consequence of this close application to study, the children used to long for Sunday to come round, in order that they might indulge themselves a little longer in bed. No amount of lessons, however, could detract from the happiness of a home wherein love was the dominant note, and in which each strove for the good of all; whilst as for Felix himself, no name could have been more symbolical of his true nature than that by which he was called. Nothing served to check the flow of his spirits. Both in work and play he was thoroughly in earnest—indeed, he regarded both in the same enjoyable light. He and Fanny were inseparables, and very soon after he began to compose they were often to be found laughing heartily together over Felix's attempts at improvisation upon some incident of a comical nature which had occurred during their play-hours.

Such beginnings, though small in themselves, soon led to more ambitious attempts being made to set to music short humorous dialogues, so as to make little operas. To write an opera, however, was not enough—it must be performed, in order to ascertain how it would go. This was a serious matter, and one calling for the services of several performers—a miniature orchestra, in fact—with singers to undertake the various parts. But Felix, as we have seen, was thoroughly in earnest about all that he undertook, and his earnestness enabled him to surmount even so great a difficulty as was here presented. The appearance in his character of this love of completeness must be noted, as, later on, it became one of his most strongly-marked characteristics. 'If a thing is worth doing at all, it is worth doing well,' was the saying which, even as a child, controlled all his actions; and so Felix would have his orchestra.

Love and money combined can accomplish the apparently impossible, and hence the orchestra was duly selected and engaged by the indulgent father from the members of the Court Band. To his delight—yet nowise to his embarrassment—Felix found himself in command of a company of sedate and experienced musicians, ready to follow the lead of his baton when it pleased him to take his place at the music-desk. Everything was now furnished for the performance, but the sense of completeness was not yet satisfied. There must be a better judge than the composer himself present to pass judgment on the merits of the piece, and so no less a person than Carl Zelter, the director of the Berlin Singakademie, and Felix's professor for thorough-bass and composition, was induced to undertake this delicate office, whilst a large number of friends of the family were invited for the occasion.

This was the beginning of a long and regular series of musical parties at the Mendelssohn house—parties to which, as time went on, it became a privilege to be invited, at which, indeed, hardly a musician of any note who happened to be passing through Berlin failed to put in an appearance. The picture is before us as we write—and as it must often have been recalled by those who frequented the house beside the canal—of the child-musician standing on a footstool before his music-desk, baton in hand, gravely conducting his orchestra. 'A wonder-child indeed,' as one has described him, 'in his boy's suit, shaking back his long curls, and looking over the heads of the musicians like a little general; then stoutly waving his baton, and firmly and quietly conducting his piece to the end, meanwhile noting and listening to every little detail as it passed.'

The performance of these operettas was not accompanied by action, the rule being for some one to read the dialogue at the piano, whilst the chorus were seated round the dining-table. It must not be supposed that Felix's compositions monopolised the entire time of the orchestra; though it rarely happened that the weekly concert failed to include one or more of his productions. At some of the performances all four children took part—Fanny taking the pianoforte when Felix conducted at the desk, Rebekka singing, and Paul playing the 'cello. Zelter, who was generally averse to praising any of his pupils, and, indeed, was regarded as a very grumpy personage, was a regular attendant at these performances, and never failed at the finish to speak a few words of praise or criticism. The old musician was secretly very proud of his pupil, and despite his habitual roughness of manner, Felix had a sincere affection for his master, as well as a deep respect for his judgment.

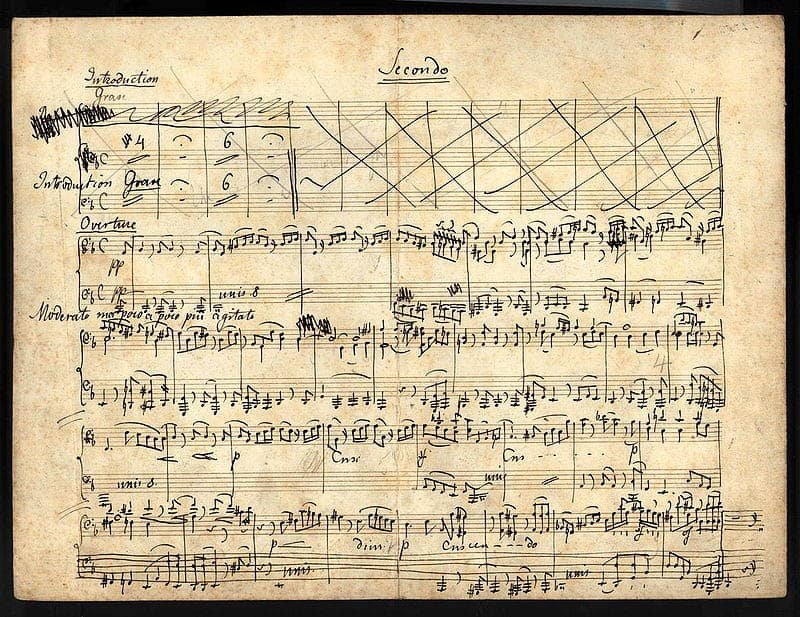

Felix was by this time composing a great deal, and, though little more than twelve years old, work of a more serious kind than the writing of operettas had been claiming his attention. To such a degree, in fact, had the flow of ideas and the facility of giving them expression developed, that within the space of a twelve-month from the completion of his twelfth year he had composed between fifty and sixty pieces, including a trio for pianoforte and strings, containing three movements (an ambitious work for a child!), several sonatas for the pianoforte, some little songs, and a comedy piece in three scenes for pianoforte and voices. Now, too, he began to collect his writings into volumes, each piece being written out with the greatest care and in the neatest of hands, with the date at which it was written, and any other note which might serve to identify the work or to show how it came to be written. Nor was this care and neatness confined to his compositions. It soon showed itself in regard to everything which he undertook—his letters, memoranda, sketches, and so forth—and the strangest part of it all is that the more he wrote and the harder he worked, the more clearly this habit of orderliness and accuracy exhibited itself. It would seem, indeed, as if for Felix Mendelssohn time was as truly elastic as some other busy folk would fain have it to be.

Hand in hand with this thoroughness in regard to work went, as we have intimated, a love of frolic and games and every species of fun that the mind of a healthy and spirited boy could devise; and with all, permeating all, was a lovability that won its way to every heart. Rarely has such a perfect combination of light-heartedness and seriousness—capacity for the hardest work and the keenest enjoyment of life—been seen as that which burst upon the world in the person of Felix Mendelssohn. The quickness with which he made friends, the firmness with which he bound those friends to himself, the constancy and affection which he lavished upon those nearest and dearest to him, were alike extraordinary.

One day a famous composer, named Carl von Weber, was walking in Berlin in company with his young friend and pupil, Jules Benedict, when the pair observed a slightly-built youth of about twelve years of age, with long, dark curls and bright, dark eyes, advancing towards them. Suddenly the boy's keen eyes sparkled with the joy of recognition, for Carl Weber had lately visited his father's house, and he had taken a great liking to him at first sight; and now, without giving the composer time to realise the fact that they had met before, Mendelssohn, with a run and a spring, had thrown his arms about Weber's neck, and was entreating him to accompany him home. As soon as the astonished musician could speak he turned to his friend, and with a comical air, half apologetic and half proud, said, 'This is Felix Mendelssohn.' The friend held out his hand with a smile. Felix gave him a quick glance, then seized the hand in both of his own. The glance and the action that followed it settled the matter—Jules Benedict and he must be friends henceforth. Weber stood by, laughing at his young friend's enthusiasm, and Felix turned to him sharply and once more begged that he and Benedict would favour him with their company. But Weber shook his head. He had to attend a rehearsal—he had come to Berlin for that purpose. 'A rehearsal!' exclaimed Felix disappointedly, and then the next moment his eyes flashed. 'Is it the new opera?' he asked excitedly. Weber nodded. 'Oh,' said Felix thoughtfully; then, indicating Mr. Benedict, 'Does he know all about it?' he inquired. 'To be sure he does,' assented the composer laughingly—'at least, if he doesn't he ought to, for he has been bored enough with it already.' Felix passed unnoticed the last part of Weber's speech. It was enough for him that young Benedict was familiar with what he himself was dying to know. He therefore seized Benedict by the arm, exclaiming, 'You will come to my father's house with me, will you not?' There was no refusing the appeal in those eyes, and the young man acquiesced willingly. Then Felix dragged Weber down for a parting embrace, and, taking his new friend by the hand, as if fearful that he might change his mind, he pulled him away.

The distance to the house was short, but Mendelssohn's impatience could only be met by his companion's consenting to race him to the door. On entering he retained Benedict's hand tightly in his grasp, conducted him at once upstairs, and, bursting into the drawing-room, where his mother was seated at her knitting, he exclaimed, 'Mamma, mamma! Here is a gentleman, a pupil of Carl Weber's, who knows all about the new opera, "Der Freischütz!"'

If Benedict had expected a more formal introduction to Madame Mendelssohn he had reckoned without a knowledge of Felix's enthusiasm. But the mother knew and understood, and the young musician not only received a warm welcome, but found it impossible to take his leave until he had complied with his new friend's request that he would seat himself at the piano and play as many airs from the great opera as he could remember at such short notice, Felix listening, meanwhile, with rapt enjoyment.

The acquaintance thus begun awakened a mutual regard in Mendelssohn and Benedict, for the latter shortly afterwards paid a second visit to the house. On this occasion he found Felix engaged in writing out some music, and inquired what it was. 'I am finishing my new quartet for piano and stringed instruments,' was the reply, gravely spoken, and without the least self-consciousness. Benedict glanced at the work in surprise. He did not know Mendelssohn yet. It was the 'First Quartet in C Minor,' which, later on, was published as 'Opus I.' 'And now,' said Felix, laying aside his pen, 'I will play to you to convince you how grateful I am for your kindness in playing to us last time.' He thereupon sat down and played with precision several of the airs from 'Der Freischütz' which Benedict had played on his previous visit. 'You see, I have not forgotten the pleasure you gave me,' he said, with a smile, as he rose from the piano. 'But now,' he added, as a new thought entered his mind, 'I want you to see the garden, please.' Down they went, and in a moment Mendelssohn had thrown off the musician's cloak, and was a boy again. With a bound he leapt over a high hedge, turned, and cleared it a second time, and then challenged his companion to a race. Another moment he burst out with a song, as if the open air had incited him to imitate the birds, and then, pointing to a favourite tree, he ran to it and climbed it like a squirrel.

These meetings took place in the summer of 1821, a year which brought much happiness to Felix, for ere it had drawn to a close he had found a new friend. When the autumn came round, Zelter announced that he was going to pay a visit of respect to his old friend and master, Goethe, the aged poet of Weimar, and he was willing to take Felix with him. Needless to say, Felix and his parents were equally delighted with the proposal. The boy had so often heard Zelter speak of Goethe, whose works, moreover, he was always quoting, that he felt he already loved the master almost as much as Zelter did himself. Goethe's house at Weimar was regarded as a shrine at which his countless admirers were wont to pay homage, even though their devotion often met with no further gratification than was to be derived from gazing at its walls or peeping into the grounds, which were sacred to the poet's footsteps. Hence the promise of an introduction to one who was the object of so much hero-worship stirred the heart of Felix to its depths, and filled his mind with reverential emotions such as few events could have had the power to awaken in one so sensible of what was due to a great and lofty intellect.

It was a bright November day when Zelter and his pupil set forth upon their journey. Both were looking forward to the meeting, though with somewhat different feelings. What Mendelssohn's feelings were we have tried to imagine, but Zelter was nursing within himself a certain pride and confidence in the prospect of introducing his favourite pupil to so keen a judge as Goethe, which he would not have revealed to that pupil for worlds. Felix's spirits, however, were so high on this occasion that Zelter had enough to do to satisfy all his questions without allowing his usually taciturn nature to relax under the sunshine of the boy's enthusiasm.

On arriving at Goethe's home they found the poet walking in his grounds. The meeting was simple and affectionate. Goethe greeted Felix with every show of kindness, and sent the boy to bed with an overflowing heart and a mind resolved upon cherishing the minutest details of this happy encounter. The next day he was to play to Goethe, and at an early hour of the morning he was sauntering in the grounds, awaiting the poet's arrival, and feasting his eyes upon the scenes which were the accustomed haunts of the author of 'Faust'; and then, selecting a sunny spot, he sat down to write a long letter home, full of description of the events of the previous day.

Nothing short of the severest of tests would satisfy Goethe of the truth of what Zelter had privately conveyed to him regarding his pupil's talents. Accordingly, sheet after sheet of manuscript music was selected by the poet from his store and placed upon the music-desk to be played by Felix at sight. The manner in which he performed his task, the ease with which he overcame the difficulties presented by penwork of various styles, and often far from clear, astonished and delighted the assembled company. But their manifestations of delight were far more pronounced when Felix, taking one of the airs which he had just played as a theme for extemporisation, exhibited in a most charming fashion, and with true musicianly feeling, the capacities of the subject for varied treatment. Still Goethe withheld his praise, and, interrupting the applause, declared that he had a final test to propose which, he jokingly warned Felix, would infallibly cause him to break down. Thus speaking, the poet placed on the desk a sheet of manuscript which at first sight was enough to strike terror and dismay into the stoutest heart, for it seemed to consist of nothing else than scratches and splotches of ink, interspersed with smudges. Mendelssohn glanced at it, and then, bursting into a laugh, exclaimed: 'What writing! How can it be possible to read such manuscript?' Suddenly he became serious, and bent to examine the writing more closely, Goethe looked triumphantly round at the company. 'Now, guess who wrote that!' he said. Zelter rose from his place beside the pianoforte, and, looking over Felix's shoulder, cried out: 'Why, it is Beethoven's writing! One can see that a mile off! He always writes as if he used a broomstick for a pen, and then wiped his sleeve over the wet ink!'

Mendelssohn could decipher the manuscript only by degrees, having to search the sheet to find the successive notes; but when he reached the end he exclaimed, 'Now I will play it to you,' and this time he played it through without a mistake. Upon this Goethe let him off, and rewarded him with some kind words of praise. Thenceforth, until the visit came to an end, Felix was called upon to play to the poet every day, and the two became fast friends. The old man treated the boy as if he were a son, laughed and joked with him, and was never so happy as when he was near. It was altogether a delightful visit, and Goethe would only part with Felix on the understanding that they should meet again very soon.

The following summer brought a new happiness to Felix, for it had been decided that the entire family should make a tour through Switzerland. In those days a journey of such length was an undertaking of much consequence, more especially when, as in this case, the family were accompanied by the children's tutor and the doctor, in addition to several servants. It was an essential part of the father's scheme of education that his children's minds should be widened by travel, and more particularly that they should make personal acquaintance with the classic ground of history—advantages which wealth enabled him to place at their command. It was with light spirits that the party set out on their journey, Felix keenly alive to every fresh scene or incident as it presented itself, and there were few of either that failed to leave their stamp upon his impressionable mind. To his insatiable curiosity must be attributed the adventure which befell him on the very first day of their travel. They had to change carriages at Potsdam, and when the horses had traversed three German miles of road from that town Felix was suddenly missed, and a brief colloquy elicited the melancholy fact that the boy had been left behind at Potsdam. The tutor thereupon turned back in one of the carriages, whilst the rest proceeded to the next stopping-place. In the course of an hour he returned with the truant seated by his side, dusty and footsore, but otherwise as fresh as when he had started. He had, it appeared, strayed from the party at Potsdam, and returned to the starting-place in time to see the carriages disappearing in the distance enveloped in a cloud of dust. He began to run, but seeing that he could not overtake them, he abated his speed, and determined to perform the journey to Brandenburg on foot. A little peasant-girl joined him. They broke stout walking-sticks from the trees at the road-side, and together marched on cheerfully, conversing as they went, until the tutor's carriage met them about a mile from the next halting-place.

It was a most delightful tour, enjoyed by all concerned, and long to be treasured by the young musician, to whom Interlaken, Vevey, and Chamounix, with their mountains, lakes, glaciers, torrents, and valleys, their sunrises and sunsets, presented a panorama of endless enchantment. Amidst the constant demands upon the senses there was little time for actual composition, but two songs and the beginning of a pianoforte quartet were inspired by the sight of the Lake of Geneva and its beautiful surroundings. Nor was the journey without the pleasures afforded by meetings with many eminent people in the musical world, such as the composer Spohr at Cassel, and Schelble, the conductor of the famous Cäcilien-Verein concerts, at Frankfort. To the latter Felix exhibited his powers by an extemporisation on Bach's motets, which called forth the musician's astonished praise.

On the return journey a call was made at Weimar, in order that Abraham Mendelssohn might pay his respects to the poet, and personally acknowledge the old man's kindness to Felix. Goethe received them most kindly, and talked much with the father on the subject of the boy's future. Of Felix's playing he never seemed to get tired. There was a charm about the boy's bright presence, and a soothing restfulness in his playing which appealed to the old poet's kindlier nature in a way that few things had the power to do. 'I am Saul, and you are my David,' he said to Felix one day, when his temper had been ruffled by something that had occurred. 'When I am sad and dreary, come to me and cheer me with your music.' How much sunshine had been infused into the old man's declining days by these brief visits Felix himself could never have guessed, but he knew that he loved Goethe, and that his love was returned.

Felix's progress, not only in music, but in his other studies as well, was by leaps and bounds. Knowledge to him seemed a food for which his appetite was insatiable, difficulties to him were but spurs to increased effort, and the effort itself appeared to be inappreciable. It was impossible to regard any longer as a boy one who possessed knowledge and powers that entitled him to take rank with performers and composers of the day. Too soon for some of those who loved him had Mendelssohn passed from his childhood stage, landing almost at a single bound into that of advanced youth, if not, indeed, into manhood itself. The Swiss tour had in a measure bridged over the interval; for when he returned it was with a taller and robuster frame, more strongly marked features, and a new and indefinable expression that was the result of widened experience, and, last of all, without the beautiful curls which had helped to make the child's face what it had been. With these changes, however, his happy boyish nature remained as strong and as irrepressible as ever. And so we pass on to the date when the transformation of which we have spoken found a fitting opportunity for recognition by his friends.

It was the night of February 3, 1824, Felix's fifteenth birthday, and the family and guests were gathered around the supper-table. Earlier in the evening there had been a full rehearsal of his first full-grown opera in three acts—'Die beiden Neffen, oder der Onkel aus Boston' (The Two Nephews, or the Uncle from Boston), which had gone most successfully, and now Zelter held up his hand as a signal that he had something important to say. All eyes were turned to him, and the clatter of tongues ceased in a moment. The old musician's face was lighted up by a most unusual expression. His grumpiness had cleared away, and a look of benevolence beamed from his eyes, in which there was even a suspicion of moisture, as, lifting his glass on high, he said:

'I have a toast to propose which I make no doubt you will acquiesce in most readily. I raise my glass to the health and happiness of my late pupil (no one failed to note the emphasis on the word 'late'), 'Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy!'

The toast was honoured with enthusiasm, and then Zelter, rising from his seat, took Felix by the hand and addressed him in these words:

'From this day, dear boy, thou art no longer an apprentice, but an independent member of the brotherhood of musicians. I proclaim you "assistant" in the names of Mozart, Haydn, and old Father Bach!'

He then embraced Felix with much tenderness, imprinting a hearty kiss on both his cheeks; and, the little ceremony ended, the company toasted the proclamation of independence with great merriment, following it up with the singing of songs by Zelter and others.

Notwithstanding that Mendelssohn had thus received his initiation into the 'brotherhood,' and that Zelter had plainly shown that he had nothing more to teach him, Abraham Mendelssohn still had some lingering doubts as to the advisability of his son's choosing music as a profession. This attitude arose quite as much from Felix's all-round knowledge and attainments as from any particular misgivings regarding the steadfastness of his love for music, or the continued development of his genius in that direction. Abraham clearly perceived that Felix had in him the makings of a man of business; he was methodical, quick, and shrewd, and possessed that infinite capacity for taking pains which is the accompaniment of true genius. These were qualities pre-eminently fitting him for a successful business career, and hence the doubtings as to whether such a rare combination of qualifications ought to be expended in following up a branch of art that might in the end prove fruitless of solid results. The father must be forgiven for entertaining such doubts, unreasonable as they may seem, when regard is paid to the absolute honesty of purpose by which his own life was governed, and the sincerity of his affection for the members of his family.

There was one man who might be trusted to give an impartial opinion on this pressing question. Cherubini, the eminent composer and musical judge, was living in Paris, and to Cherubini it was decided to apply forthwith for advice. Accordingly, Felix and his father journeyed to Paris with this object, the former being fully as anxious as his father to have the opportunity of making the acquaintance of so famous a musician, as well as of receiving at his hands the support and encouragement which would put an end, once and for all, to his father's doubts. Cherubini was hardly ever known to praise, but perhaps for this very reason his opinion was eagerly sought by young performers and composers. Of those who went to him for advice, however, by far the greater number were sent away with burning cheeks and downcast eyes. This dismal fate was not reserved for Felix, for no sooner had the great man listened to his playing of one of his own compositions than he recognised Mendelssohn's power and genius, and, turning to the father, he said with a smile; 'Sir, the boy is rich; he will do well.' After some further tests Cherubini expressed himself as perfectly satisfied with regard to Felix's future, and when father and son returned to Berlin it was with the settled conviction on the part of the former that thenceforward the boy's life must be devoted to music.

And now a great change came into the daily life of the family. The house in the Neue Promenade was exchanged for a statelier and more commodious mansion, No. 3, Leipziger Strasse, situated on the outskirts of the city near the Potsdam Gate. The grounds of the new house adjoined the old deer-park of Frederick the Great, and in themselves were almost large enough to be styled a park. Stretches of green turf, shaded by fine forest-trees, winding walks amidst sweet-scented flowering shrubs, and arbours nestling in retired corners, inviting retreats for study and meditation, comprised an ideal spot for one who loved the surroundings of Nature. Nor was the house itself behindhand in offering special attractions for the purposes of study and recreation, in addition to the more solid requirements of comfort and accommodation. The rooms were spacious and elegant, and comprised one large apartment perfectly adapted for musical or theatrical entertainments. But, just as there are not a few of us who, in choosing a residence, are drawn towards the garden before proceeding to investigate the dwelling itself, so Felix's delight was first of all expressed with regard to the beautiful surroundings of the new home. And there was one feature of the garden which opened up to his mind splendid possibilities in connection with his beloved pursuit. This was a garden-house, containing a central hall capable of accommodating several hundred people, and furnished with windows and glass doors opening and looking upon the lawns and trees. The garden-house was as essentially a part of the garden as any large summer-house could be, and yet comprised sufficient rooms to fit it for occupation as a separate dwelling if such were necessary.

No sooner had the family established itself in the new home than the musical and artistic gatherings were resumed on an even larger scale than heretofore. The Sunday concerts were held in the 'Gartenhaus,' which, on most of the other evenings of the week, was the resort of friends, both old and young, who came to listen to the music, or to play or act, or in other ways amuse themselves. So famous did these gatherings become, and so completely were the mansion and its surroundings identified with the family which occupied it, and dispensed its open-handed hospitality, that it was impossible to mention the Leipziger Strasse without connecting it with information respecting the Mendelssohns. The two things, indeed, were inseparable in everybody's mind. Thither, amongst others, came Ferdinand Hiller, the eminent performer, who had visited Beethoven while the latter lay on his death-bed, and whose friendship with Felix had begun at Frankfort a short time before. Moscheles, who had worked under Beethoven, also became a regular visitor at the house, and one of Felix's closest friends. Moscheles had already acquired fame as a player, and during his stay in Berlin he was induced, though not without reluctance, to give some lessons to Mendelssohn. 'He has no need of lessons,' he remarked, with reference to Felix's ability. 'If he wishes to take a hint from me as to anything new to him, he can easily do so.' Felix, however, frankly acknowledged afterwards how much he owed to these lessons at the hands of him whose graceful, elegant touch could not be excelled. Speaking of Moscheles' playing on one occasion, Mendelssohn said that 'the runs dropped from his fingers like magic.'

We must now speak of two works which were composed very soon after Zelter's declaration of his pupil's independence. The first of these was an Octet for stringed instruments, designed as a birthday present for Edward Ritz, the young violinist, for whom Mendelssohn entertained a deep affection, and whose premature death caused him much sorrow. Felix had not completed his seventeenth year when the Octet was written. He had already composed a great deal, but he had done nothing so entirely fresh and original as this. Indeed, one might place one's finger on the Octet, and, forgetting everything which he had written before, say with emphasis and truth: 'This is Mendelssohn himself; this is his very own.' No longer an 'apprentice,' swayed or, at least, influenced by the masters who had gone before him, he has here given us the first-fruits of his 'assistantship' in a work which expresses his own musicianly feelings, and in which we get our first glimpse of his true genius. The whole piece was intended to be playedstaccato and pianissimo. It has a fleeting, spiritual, and fairy-like effect, with 'tremolos and trills passing away with the quickness of lightning.' The Scherzo is especially beautiful, and Mendelssohn admitted to his sister Fanny that he had taken as his motto for this movement a stanza from Goethe's Walpurgis-night Dream in 'Faust':

'Floating cloud and trailing mist

Bright'ning o'er us hover;

Airs stir the brake, the rushes shake—

And all their pomp is over.'

We are reminded of this in the last part, where 'the first violin takes a flight with a feather-like lightness, and all has vanished.'

But if the Octet serves to mark a distinct stage in the development of Mendelssohn's genius, what are we to say of the work which followed it? Several things had paved the way for this new composition. To begin with, Felix and Fanny made their first acquaintance with Shakespeare in this year through the medium of a German translation, and they fell completely under the spell of 'A Midsummer Night's Dream.' Then the summer proved to be an exceptionally fine one, and led to many hours being spent in the beautiful garden—in fact, there is no doubt that the garden began it. It is not difficult to imagine how the romantic mind of Felix was stirred by reading this delightful fairy play amidst such charming surroundings. To read thus was to picture in music, to give a musical setting to both scene and action, at first indefinite, shadowy, suggestive, but as reading and thinking progressed, growing ever stronger and more clearly defined. Thus, stretched upon the turf, book in hand, the silence broken only by the singing of the birds and the humming of the bees, the music of the Overture to 'A Midsummer Night's Dream' gradually shaped itself in Mendelssohn's mind, until what at the beginning had in itself been little more than a dream, became a tangible creation.

When the Overture had been written down, it was frequently played by Felix and Fanny as a duet. In this simple form Moscheles heard it for the first time, and he was struck by the force of its beauty. The work was elaborated and perfected by degrees, until the day arrived when it was performed by the garden-house orchestra before a crowded audience. So great was the reception accorded to the overture on this occasion that in the February following Felix journeyed to Stettin to conduct the first public performance.

When we listen to this beautiful work, we are constrained to admit that no happier introduction to the play could have been devised; for just as the play itself seems to demand for its environment some lovely garden or woodland glade, so Mendelssohn's music conjures up visions of the fairy scenes of enchantment with which the play abounds. It is a work instinct with musicianly feeling, and its strength is borne out by the soundness and skill displayed in its construction. As a great musical judge has said of it: 'No one piece of music contains so many points of harmony and orchestration that had never been written before, and yet none of them have the air of experiment, but seem all to have been written with certainty of their success.'

But we must not linger over this portion of our story, though we are tempted to do so; for there can be no doubt that these years spent in the Leipziger Strasse house, when the members of the family were all together, each contributing his or her share to the intellectual intercourse that went on beneath its hospitable roof, afford the happiest pictures of Mendelssohn's young life. It was so full and many-sided a life, hard work alternating with gymnastics, dancing, swimming, riding, and, of course, music, each occupation pursued with such zest and heartiness as to convey the impression at the moment of its being the most absorbing of all.

Amidst these pleasures, however, a new project had taken hold of his mind, one which, like many another great undertaking fraught with far-reaching results, owed its inception to the feeling aroused by the indifference and lack of sympathy shown by others towards what he himself believed to be deserving of the highest praise. Two years before, Felix's grandmother had presented him with a manuscript score of Bach's 'Passion according to St. Matthew,' which Zelter had permitted to be copied from the manuscript in the Singakademie. A more devoted lover of Bach's music than Zelter could not have been found, and the old man had infused some of this love into his pupil; consequently, when the score of the 'Passion' was placed in Mendelssohn's hands, he set to work to master it, and with such earnestness had he applied himself to the study that at this point of our story he knew the whole of it by heart.

The more he studied this great work, the more was he impressed by its beauty and the grandeur of its conception. Could it possibly be true, he asked himself, that throughout the length and breadth of Germany so stupendous a work as this remained unheard, unknown? that a creation so deathless in itself could be permitted to sleep without even the hope of an awakening? 'Alas!' replied Zelter, when the question was put to him—'alas! it is nearly a hundred years since old Father Bach died, and though his name lives, as all great names must live, the majority of those who speak of him as a master are ignorant of the works which made him great; they have forgotten, if, indeed, they ever heard, the sound of the master's voice!'

Here, then, in the apathy manifested in regard to Bach's greatest works, Mendelssohn found the stimulus that was needed. If only this state of things could be changed, if only he might be permitted to show the way to an understanding and appreciation of these priceless treasures! Towards this great end something, at least, might be accomplished by the force of example. As we have seen, he knew the 'Passion' music by heart, and he now proceeded to enlist others in a study of the work. In a short time he had got together sixteen carefully selected voices, and had arranged for his little choir to meet once a week at his house for practice. It was a small beginning, but his own enthusiasm soon infected the rest, and they all grew deeply earnest in their work—so earnest, indeed, that ere long the yearning had seized them for a public performance. The Singakademie maintained a splendid choir of between three hundred and four hundred voices. If only the director could be induced to allow a trial performance to be given under Mendelssohn's conducting! Much as he personally desired such a consummation of their labours, however, Felix felt convinced that he knew Zelter only too well to indulge any hopes that he would sanction so great an undertaking. Zelter had no faith in the idea that public support would be given to a revival of the 'Passion,' and Felix well knew that nothing would shake him in this opinion. But this conclusion was strongly opposed by a prominent member of the Garden-house choir, a young actor-singer named Devrient, who insisted that Zelter ought to be approached on the subject; and as he himself had been a pupil of Zelter, and possessed the gift of eloquence in no small degree, he succeeded in persuading Mendelssohn to accompany him on a visit to the director's house.

Accordingly, the pair set forth early one morning to brave the old giant in his den, Mendelssohn haunted by a dread of the manner in which their proposals would be received, and Devrient, who was to be spokesman, keeping up a bold front, and assuring his friend that they would ultimately succeed.

They found Zelter seated at his instrument, with a sheet of music-paper before him, a long pipe in his mouth, and enveloped in a cloud of tobacco-smoke. In response to his gruff inquiry, what had brought them at so early an hour, Devrient unfolded his plan by degrees, beginning by enlarging upon their admiration for Bach's music, with a gentle reminder to Zelter that this taste had been acquired under his own guidance, and proceeding to dwell upon the progress of their studies and the yearning which they all felt for a public trial of the work, and concluding with an eloquent appeal for assistance from the Academy itself.

Zelter listened with an outward show of patience that was as extraordinary as it had been unlooked for, but his eyes gleamed through the clouds of smoke with a light that foreboded a speedy outburst of his slumbering fires. Nevertheless, when he began to speak, it was not to condemn the young men for their presumption, but to point out that the difficulties in performing such a work at that time were inconceivably greater than they had supposed. In Bach's time it was different, the Thomas School could supply what was necessary—the double orchestra, double chorus, and so forth; but now such things were insuperable difficulties; nothing could overcome them.

As he spoke he laid aside his pipe, and rising from his chair, paced excitedly to and fro, repeating again and again: 'No, no; it is not to be thought of; it is mad, mad, mad!' To Felix he looked the picture of a shaggy old lion stirred up by his keeper. Still Devrient persevered. He even ventured to say that they had considered those difficulties; that they did not believe them to be insuperable; that they had implicit faith in their own enthusiasm having the power to kindle the like in others; and, finally, that with the Academy's co-operation success must ensue.

Zelter grew more and more irritated as Devrient proceeded, and Felix, observing the growing anger in his eye, plucked his companion by the sleeve, and edged nearer to the door. At length the explosion came. 'That one should have the patience to listen to all this! I can tell you that very different people have had to give up attempting this very thing, and yet you imagine that a couple of young donkeys like yourselves will be able to accomplish it!'

Felix by this time was at the door, feverishly beckoning to Devrient to come away, but his friend refused to budge; he even began afresh. He pleaded in his most telling tones that, inasmuch as it was Zelter himself who had awakened their love for the master, the honour would be to him quite as much as to themselves if his pupils succeeded in bringing about this grand result, and how well-deserved and fitting a crown this would be to his long career, this honour and testimony to the greatness of Father Bach.

Felix opened his eyes wider in astonishment; but there could be no mistake—the crisis had passed, and Zelter was visibly weakening; the lion died out of his eyes, the pipe once more found its way to his lips, and after many demurs, many arguments, much pacing up and down, Zelter with a sigh of relief gave in. It was a noble surrender, for it included a promise of all the help that he could give, and the young enthusiasts quitted the lion's den triumphant.

'You are a regular rascal, an arch-Jesuit!' said Felix to his friend as they descended the stairs.

'Anything you like for the honour of Sebastian Bach!' retorted the other as they stepped out into the keen, wintry air.

How Mendelssohn grappled with this great work; how he threw into it all the energy he possessed; how he mastered its every detail, and gave it life; how, with infinite tact and patience, he made it a living, dramatic masterpiece in the eyes of those who were to perform it; how the rehearsals at the Academy were thronged by professionals and amateurs desirous of realising its true nature and power; how at length the first public performance of the 'Passion according to St. Matthew' since the composer's death took place at the Singakademie, with Mendelssohn conducting, on March 11, 1829, and how every ticket was sold, and fully a thousand disappointed ones were turned away from the doors—all this must be read elsewhere. Suffice it here to say that this performance marked the beginning of a great revival—the awakening throughout Germany and England of a love and appreciation of Bach which has never since faded or diminished.

It was in connection with this work that Mendelssohn made the first and only allusion to his Jewish descent. 'To think,' he remarked to Devrient, with a look of triumph in his eyes as they were walking together to the final rehearsal—'to think that it should have been reserved for an actor and a Jew to restore this great Christian work to the people!'

The excitement attending the performance, with its repetition on March 21, the anniversary of Bach's birth, had not subsided ere Mendelssohn was engaged in taking leave of his dear ones prior to embarking at Hamburg on his first visit to England. Several circumstances had combined to render the present a favourable moment for undertaking the journey. The Moscheleses, and another friend named Klingemann, who had been a constant visitor at the Berlin house until called away to occupy a London post, had assured him of a warm welcome; it was his father's wish, shared by Zelter also, that he should travel, and he for his own part was desirous of showing that he could support himself by music. Abraham Mendelssohn had, indeed, designed this visit as the first portion of a lengthened tour which would enable Felix to see more of various countries, and assist him in choosing that which offered the best opportunities for his life-work.

The London musical season was at its height when he arrived, but his first letters home were chiefly occupied with descriptions of the city itself, and how it had affected him. 'It is fearful! it is maddening!' he writes to Fanny three days after he had settled into his Great Portland Street lodgings. 'London is the grandest and most complicated monster on the face of the earth.... Things roll and carry me along as in a vortex. Not in the last six months at Berlin have I seen so many contrasts and such variety as in these three days.... Could you see me at the exquisite grand-piano which Clementi has sent me for the whole of my stay here, by the cheerful fireside' (the open grate fire was a novelty to one who had come from the land of closed stoves), 'in my own four walls ... and could you see the immense four-post bed in the next room in which I might go to sleep in the most literal sense of the word, the many-coloured curtains and quaint furniture, my breakfast-tea with dry toast still before me, the servant-girl in curl-papers, who has just brought me my newly-hemmed black necktie, and asks what further orders I have ... and could you but see the highly respectable, fog-enveloped street, and hear the pitiable voice with which a beggar down there pours forth his ditty (he will soon be outscreamed by the street-sellers), and could you picture to yourselves that from here to the City is three-quarters of an hour's drive, and that in all the cross streets of which one has glimpses the noise, clamour, and bustle are the same, if not greater, and that after that one has only traversed about a quarter of London, then you might understand how it is that I am half distracted!'

The London musical season was at its height when he arrived, but his first letters home were chiefly occupied with descriptions of the city itself, and how it had affected him. 'It is fearful! it is maddening!' he writes to Fanny three days after he had settled into his Great Portland Street lodgings. 'London is the grandest and most complicated monster on the face of the earth.... Things roll and carry me along as in a vortex. Not in the last six months at Berlin have I seen so many contrasts and such variety as in these three days.... Could you see me at the exquisite grand-piano which Clementi has sent me for the whole of my stay here, by the cheerful fireside' (the open grate fire was a novelty to one who had come from the land of closed stoves), 'in my own four walls ... and could you see the immense four-post bed in the next room in which I might go to sleep in the most literal sense of the word, the many-coloured curtains and quaint furniture, my breakfast-tea with dry toast still before me, the servant-girl in curl-papers, who has just brought me my newly-hemmed black necktie, and asks what further orders I have ... and could you but see the highly respectable, fog-enveloped street, and hear the pitiable voice with which a beggar down there pours forth his ditty (he will soon be outscreamed by the street-sellers), and could you picture to yourselves that from here to the City is three-quarters of an hour's drive, and that in all the cross streets of which one has glimpses the noise, clamour, and bustle are the same, if not greater, and that after that one has only traversed about a quarter of London, then you might understand how it is that I am half distracted!'

One needs to be something of an artist as well as of a poet to appreciate London at her true worth, and Mendelssohn possessed both qualities in no small degree; hence it is only natural that the artistic and poetical aspects of our city should have appealed most strongly to his sensitive nature. A few days later he writes: 'I think the town and the streets are quite beautiful. Again I was struck with awe when yesterday I drove in an open carriage to the City along a different road and everywhere found the same flow of life ... everywhere noise and smoke, everywhere the end of the streets lost in fog. Every few moments I passed a church, or a market-place, or a green square, or a theatre, or caught a glimpse of the Thames.... Last, not least, to see the masts from the West India Docks stretching their heads over the housetops, and to see a harbour as big as the Hamburg one treated like a mere pond, with sluices, and the ships arranged not singly, but in rows, like regiments—to see all that makes one's heart rejoice at the greatness of the world.'

The magnificence of a ball at Devonshire House reminds him of the 'Arabian Nights.' The Duke of Wellington and Sir Robert Peel were present, and he describes the beauty of the girls dancing, the lights, the music, the flowers, etc. 'To move among these beautiful pictures and lovely living forms, and to wander about in all that flow of life and universal excitement, perfectly quiet and unknown, and unnoticed and unseen, to notice and to see—it was one of the most charming nights I remember.' Again, of a fête held at the Marquis of Lansdowne's, he says: 'That such magnificence could really exist in our time I had not believed. These are not parties—they are festivals and celebrations.'

In the mind of Mendelssohn, therefore, London struck a sympathetic chord, and the pleasure which he felt on entering the city was heightened by the warmth of the welcome which he received at the hands of the musical public. His first appearance was at the Argyll Rooms, in Regent Street, at a concert of the Philharmonic Society on May 25, when his 'Symphony in C minor' was performed. He gives a full description of the rehearsal and performance in his letter to Fanny:

'When I entered the Argyll Rooms for the rehearsal of my Symphony, and found the whole orchestra assembled, and about two hundred listeners, chiefly ladies, strangers to me, and when, first, Mozart's "Symphony in E flat major" was rehearsed, after which my own was to follow, I felt not exactly afraid, but nervous and excited. During the Mozart pieces I took a little walk in Regent Street, and looked at the people; when I returned, everything was ready and waiting for me. I mounted the orchestra, and pulled out my white stick which I have had made on purpose (the maker took me for an alderman, and would insist on decorating it with a crown). The first violin, François Cramer, showed me how the orchestra was placed—the furthest row had to get up so that I could see them—and introduced me to them all, and we bowed to each other; some, perhaps, laughed a little that this small fellow with the stick should now take the place of their regular powdered and bewigged conductor. Then it began. For the first time it went very well and powerfully, and pleased the people much, even at rehearsal. After each movement the whole audience and the whole orchestra applauded (the musicians showing their approval by striking their instruments with their bows and stamping their feet). After the finale they made a great noise, and as I had to make them repeat it, because it was badly played, they set up the same noise once more; the directors came to me in the orchestra, and I had to go down and make a great many bows. Cramer was overjoyed, and loaded me with praise and compliments. I walked about in the orchestra, and had to shake at least two hundred different hands. It was one of the happiest moments within my recollection, for one half hour had transformed all those strangers into friends and acquaintances. But the success at the concert last night was beyond what I could ever have dreamed. It began with the Symphony; old François Cramer led me to the piano like a young lady, and I was received with immense applause. The Adagio was encored; I preferred to bow my thanks and go on, for fear of tiring the audience, but the Scherzo was so vigorously encored that I felt obliged to repeat it, and after the finale they continued applauding, while I was thanking the orchestra and shaking hands, and until I had left the room.'

On another occasion, when he was to perform at a concert, he describes how he went to the room early in order to try the piano, which was a new one. He found the instrument locked, and dispatched a messenger for the key. In the meantime he seated himself at another piano of ancient aspect, and beginning to extemporise soon became lost in reverie. The empty room, the 'old grey instrument which the fingers of several generations may have played,' and the silence affected him so deeply that he forgot the passing time, until he was reminded of the approach of the concert hour by the people coming in to take their seats. When, having first put himself into grande toilette—very long, white trousers, brown silk waistcoat, black necktie, and blue dress coat—he mounted the orchestra he felt nervous; a panic seized him, for the hall was crowded, ladies even sitting in the orchestra who could not get places in the room. 'But as the gay bonnets gave me a nice reception, and applauded when I came ... and as I found the instrument very excellent and of a light touch, I lost all my timidity, became quite comfortable, and was highly amused to see the bonnets agitated at every little cadenza, which to me and many critics brought to mind the simile of the wind and the tulip-bed.'

A dinner-party followed the concert, and then he went to visit some friends living out of town with whom he was to spend the night. Finding no carriage to convey him, he set out to walk through the fields in the cool of the evening. Can we not picture him crossing the still meadows by a lonely path, meeting no one, the air redolent of spring flowers, musical ideas floating through his mind—ideas which there was nobody to hear, which nobody, perhaps, was ever destined to hear, as he sang them aloud in the fading light, 'the whole sky grey, with a purple streak on the horizon, and the thick cloud of smoke behind him.'

Amidst the round of work and the pressure of invitations which made up the sum of his daily life in London, the love of boyish fun, which formed a wholesome counteraction to his serious moods, broke out every now and then with its old accustomed force, eclipsing for the moment the memories of stately dinner-parties and receptions. One night when in company with two friends he was returning from what he terms 'a highly diplomatic dinner-party' at the Prussian Ambassador's, where they had taken their 'fill of fashionable dishes, sayings, and doings,' they passed a very enticing sausage-shop in which some German sausages were exposed in the window. A wave of patriotism overcame them; they entered, and each bought a long sausage, and then the trio turned into a quiet street to devour them, accompanying the meal with a three-part song and shouts of laughter.

Mendelssohn's heart was easily touched by the distresses of others, and when he learnt of the sufferings of those who had lost their all in the floods in Silesia at this time, he set to work at once to arrange a concert in their behalf. The 'Midsummer Night's Dream Overture' formed one of the items of the programme—this being the second occasion of its performance since his arrival. It was most enthusiastically received, and, indeed, the whole concert was a great success. The room was so besieged that no fewer than one hundred persons were turned from the doors. Ladies who could not find seats in the body of the hall crowded upon the orchestra, and Mendelssohn was delighted at receiving a message from two elderly ladies, who had strayed between the bassoons and the French horns, anxiously inquiring 'whether they were likely to hear well!' Another enthusiastic lady esconsced herself contentedly upon a kettledrum. There could be little doubt that the overture had secured a firm hold upon English hearts at its first hearing. Jules Benedict, who was present on the occasion, describes the effect upon the audience as electrical. At the end of the first performance a friend who had taken charge of the precious manuscript was so careless as to leave it in a hackney-coach on his way home, and it was never recovered. 'Never mind,' said Mendelssohn, when the loss was reported to him, 'I will write another.' And he sat down at once and rewrote the score entirely from memory, and when the copy was afterwards compared with the parts it was found that he had not made a single variation.

From London, when the season came to an end, he went in company with his friend Klingemann to Scotland, his keen sense of perception drinking in all the variety and charm which the tour presented, and his genius supplying a musical setting to whatever struck him as specially beautiful. The ruined chapel attached to the old Palace of Holyrood, seen in the twilight, with its broken altar at which Mary received the Scottish crown, overgrown with grass and ivy, and its mouldering, roofless pillars, with patches of bright sky between, gave him the first inspiration for his Scotch Symphony. But it was the Hebrides which, in their lonely grandeur and bleakness, affected him most of all. Of Iona, with its ruins of a once magnificent cathedral, and its graves of ancient Scottish Kings, he writes that he shall think when in the midst of crowded assemblies of music and dancing. Of Staffa, again, with its strange, basaltic pillars and caverns, he says: 'A greener roar of waves surely never rushed into a stranger cavern—its many pillars making it look like the inside of an immense organ, black and resounding, and absolutely without purpose, and quite alone, the wide, grey sea within and without.' How deeply the Hebrides impressed him he shows by a few lines of music added to his letter, which he says were suggested to him by the sight of these lonely sister isles. Later on this very piece of music formed the opening to his 'Overture to Fingal's Cave.'

How thoroughly music entered into his daily life and permeated his thoughts, we may know from his habit of seating himself at the piano in the evening, and improvising music to express what he had bothseen and felt throughout the day. To Mendelssohn music was a natural language by which he could express, in the most perfect manner, the emotions which had been aroused by reading or by the contemplation of Nature. Thus, when he went from Scotland to North Wales to stay with some friends named Taylor, he wrote for Susan Taylor a piece called 'The Rivulet,' which was a representation of an actual rivulet visited by them in their rambles. Again, Honora Taylor had in her garden a creeping plant (the Eccremocarpus), bearing little trumpet-shaped flowers, and Mendelssohn was taken with a fancy for inventing the music which the fairies might have been supposed to play on those tiny trumpets. The piece was called 'A Capriccio in E minor,' and when he wrote it out he drew a branch of the plant all up the margin of the paper. For another member of the family he wrote a piece which was suggested by a bunch of carnations (his favourite flower) and roses arranged in a bowl, and he put in some arpeggio passages to remind the player of the sweet scent rising up from the flowers.

Felix had just returned to London, and was contemplating an early departure for Berlin, when an injury to his knee, the result of a carriage accident, compelled him to lie up for several weeks, and hence to forego a pleasure to which he had been looking forward with feelings of eager affection. Shortly before he left home Fanny's engagement to William Hensel, a young painter of promise, had received her parent's sanction, and it had been confidently expected that Felix would return in time for the marriage. The disappointment caused by the accident was therefore keenly felt both by himself and those at home. Hensel was clever, and by no means a stranger to the gatherings at the Gartenhaus; but his entry into the select and innermost circle of the brotherhood, armed with the kind of right which his engagement to Fanny had conferred upon him, caused him to be regarded in a new light, and it was not until a little time had elapsed that he found his way to their hearts by his gentle ways, assisted in no small degree by his pencil. At first the exclusiveness of a set which had received the title of 'The Wheel,' and which prided itself on the freemasonry which obtained amongst its members, was somewhat chilling; but Hensel was not easily discouraged; he took to drawing the members' portraits as his contribution to the bonhomie of the circle, and with such success that 'The Wheel' soon came to regard him as an indispensable spoke, whilst the portraits multiplied until they formed a huge collection. Fanny's marriage, moreover, did not imply any break in the family circle, for when her brother returned to Berlin he found that Hensel and his bride had taken up their residence in the Gartenhaus.

The grand tour had practically only begun, and was now to be resumed, but the visit to England was exercising over Mendelssohn's mind a strong influence which, though not unconnected with the success and fame it had brought to him, might with more justice be ascribed to the sympathetic appreciation and kindness which he had received at the hands of the English. 'A prophet is not without honour, save in his own country,' and Berlin had so far held back the encouragement that strangers were so willing to accord him. Moreover, for one of his artistically sensitive temperament London possessed a magnetic charm that was lacking in Berlin. At home his very youth seemed to count against him, but in London it was, if anything, in his favour. The fame of his visit, however, had preceded him to Berlin, and shortly after his return he was offered the Professorship of Music at the University, an honour which he at once declined, feeling that its acceptance would not only interfere with his freedom in composition, but bind him down to an occupation which he confessed was not his forte. This Chair had been specially created in the hope that he would fill it, and it marks the first, though by no means the last, attempt on the part of the Berliners to secure his services for their city.

In the May following he set forth once more on his travels, bound for Venice, Florence, and Rome. He could not pass through Weimar, however, without paying a visit to Goethe; it proved to be the last meeting, and it was filled with incidents that left a deep impression on his mind. Never had the sympathy and friendship between the two been closer or more confidential than on this occasion. 'There is much in my spirit that you must light up for me,' said Goethe to Felix one day when they had been conversing together. Goethe called upon him continually for music, but showed an indifference towards Beethoven's works; Felix, however, insisted that he must endure some of the master, and played to him the first movement of the 'C minor Symphony.' Goethe listened for a few moments, and then said: 'That does not touch one at all; it only astonishes one.' But Felix played on, and presently, after some murmuring to himself, the poet burst out with: 'It is very great, it is wild! It seems as though the house were falling! What must it be with the whole orchestra!'

The tour was a long one, for several cities had to be visited before he could cross the Swiss frontier. Each day brought its full measure of incident and delightful sight-seeing. It was in Switzerland, however, that Mendelssohn's passionate love for Nature was stirred to its depths. His Alpine walks were a revelation of Nature in her most decided moods, and one particular walk over the Wengern Alp was destined to be long remembered. The mountain summits were glittering in the morning air, every undulation and the face of every hill clear and distinct. Formerly it was their height alone that had impressed him, 'now it was their boundless extent that he particularly felt—their huge, broad masses; the close connection of all those enormous fortresses, which seemed to be crowding together and stretching out their hands to each other.'

He loved all beautiful things, but he loved the sea best of all; it seemed to him to express in its varying moods every feeling which he himself possessed. 'When there is a storm at Chiatamene,' he wrote to Fanny when she was visiting Italy, 'and the grey sea is foaming, think of me.' And now as he approached Naples, and saw the sea sparkling in the sunlit bay, he exclaims: 'To me it is the finest object in Nature! I love it almost more than the sky. I always feel happy when I see before me the wide expanse of waters.' Again, the ancientness of Nature herself conveyed far more to him than any legend of antiquity connected with the works of man; he could not feel in 'crumbling mason work' the interest and fascination that existed for him in the unchanged outlines of the hills, or in the fact that the waves lapped the island which formed the refuge of Brutus, and the lichen-covered rocks bent over them then just as they did now. These were monuments on which no names were scribbled, no inscriptions carved, and to such he clung.

Yet in Rome itself he found a centre of unending interest and fascination. 'All its measureless delights lay as a free gift before him; every day he picked out afresh some great historic object: one day a ramble about the ruins of the ancient city, another day the Borghese Gallery or the Capitol, or else St. Peter's or the Vatican. So each day was one never to be forgotten, and this sort of dallying left each impression firmer and stronger. If Venice seemed like the gravestone of its own past, its ruinous, modern palaces and the enduring remembrance of a bygone supremacy giving it a disquieting, mournful impression, the past of Rome struck him as history itself; its monuments ennobled, and made one at the same moment serious and joyful, for there was joy in feeling how human creations may survive a thousand years and yet possess their quickening restoring, influence. Each day some new image of that past imprinted itself on his mind, and then came the twilight, and the day was at an end.'

The tour was not completed until the spring of the following year (1832), and during that interval two sad notes had been struck—the first being the death of Edward Ritz, the young violinist, Felix's closest friend, from whom he admitted that he had taken the model of his delicate, musical handwriting; and the second that of Goethe. In connection with the latter loss Felix felt deeply for Zelter, for he knew how the old man had worshipped and leant upon the master-poet. 'Mark my words,' said Mendelssohn, when he received the sad intelligence, 'it will not be long now before Zelter dies!' The words were but too prophetic, for in less than two months from the day on which they were spoken Zelter had followed the master he loved so well.

Before the latter event happened, however, Mendelssohn had returned to London. His affection for the City had now become a settled part of his nature. Even amidst the sunshine of Naples, with the glittering sea before his eyes, he had longed for London. 'That smoky nest is fated to be now and ever my favourite residence,' he writes; 'my heart swells when I think of it.' Even with the love he felt for those who were awaiting his return to the Berlin home it must have been hard for him to tear himself away from London, where his genius and his attractive personality found recognition at every turn. Consequently it is not surprising that he should have found his way back to his 'smoky nest' before very long—this time accompanied by his father. It was Abraham Mendelssohn's first visit, and it served to bring out more clearly than ever the closeness of the bond which united them. Felix nursed his father through an illness of three weeks' duration with a tenderness and solicitude that called forth a touching tribute from the patient. 'I cannot express,' writes Abraham to Leah, 'what he has been to me, what a treasure of love, patience, endurance, thoughtfulness, and tender care he has lavished on me; and much as I owe him indirectly for a thousand kindnesses and attentions from others, I owe him far more for what he has done for me himself.'

Two years later Mendelssohn was mourning the loss of this parent, whose sudden death had cast a deep gloom over a time when everything seemed to promise happily for the young composer. Only a month before the sad event Felix had joined the home-party at Berlin, and the house had once more assumed the full and complete life of its earlier days. The merriment, the joyous laughter were as hearty and resounding as they had been of yore, and there the father and mother had sat watching the fun—Abraham by this time quite blind, but keenly interested in all that was going on. Now the first definite break in that happy circle had come, shutting out the past for ever!

The extraordinary fullness which characterised Mendelssohn's life—'he lived years whilst others would have lived only weeks,' was the true remark of one who knew him well—reminds us of the impracticability of giving anything like a complete description of even its chief incidents. The stage at which our story has arrived does not, it is true, show him at the pinnacle of his fame as a composer, but if we entertained any doubts as to his greatness or his popularity at this time, we have only to imagine ourselves present at the scene which was being enacted on a certain afternoon in May, 1836, in the music-hall at Düsseldorf to be assured on both of these points. The long, low-pitched room is filled with an excited and enthusiastic audience applauding with all their might and main, for the first performance of Mendelssohn's oratorio 'St. Paul' has just come to an end. Amidst the roars of applause the ladies of the chorus have risen from their seats, and, advancing to the spot where Mendelssohn stands bowing his acknowledgments to the audience and orchestra, they shower garlands upon him, and then to complete the display they place a crown of flowers upon the score itself.

Some time before this event the town of Düsseldorf had claimed his services as director of music, and a little later Leipzig had followed suit—the latter event marking the beginning of a connection fraught with results of the highest importance to the musical world, and of much happiness to Mendelssohn himself. It was at this period that he composed many of those charming part-songs, intended for performance in the open air, that have since become such recognised favourites; of these we need only recall 'The Hunter's Farewell' and 'The Lark' as examples. But the time is marked for us in even clearer notes than these, for to this era belong several of his 'Songs without Words'—those melodies which have grown into our hearts never, we may well believe, to be uprooted. Mendelssohn not only invented the title 'Lieder ohne Worte,' but also the style of composition itself. Sir Julius Benedict remarks that 'at this period mechanical dexterity, musical claptraps, skips from one part of the piano to another, endless shakes and arpeggios, were the order of the day.' Mendelssohn, however, would never sacrifice to the prevailing taste; his desire was to 'restore dignity and rank to the instrument,' and he accordingly wrote what Sir Julius aptly describes as these 'exquisite little musical poems.'

The year of which we are speaking was productive of the deepest happiness to Mendelssohn, for it was that of his engagement to Cécile Jeanrenaud, the beautiful daughter of a French Protestant clergyman, whose acquaintance he had formed whilst on a visit to Frankfort. In the following spring they were married, and thus began for both a new life replete with happiness. In Cécile Felix found one who, out of her loving, gentle nature, could give him the sympathy and support that he needed, whilst she in turn received from her husband the fullest return that a grateful and sensitive heart, obedient to the promptings of a love that never wavered in its steadfastness and devotion, could bestow. No home life could have been happier, none more simple in its give and take of affection, than that of Mendelssohn and his wife; nothing transpired to destroy or even to obscure for a moment the halo of romance which surrounded it from the beginning, and which rendered it from first to last a marriage of love.