The Cathedral of St. Stephen, standing in the central square of Vienna, looked grey and cheerless in the misty atmosphere of a November evening. Evensong had just concluded, the worshippers had dispersed, and the great square itself was silent and deserted, save for one or two hurrying pedestrians crossing it on their homeward way. One of these, however, formed an exception to the rest, for he seemed to be in no hurry to leave the square. On reaching the further side he hesitated, glanced up at the clock, and then, turning about, paced listlessly up and down, as if uncertain whether to go or remain. Not even the rain, which now began to fall in that silent, hopeless fashion which predicts a thoroughly wet evening, appeared to assist the wanderer in coming to a decision. He was a mere stripling, short of stature, shabbily clothed, and with a keen look on his pale face that betokened a want of food and rest.

The square was dimly lighted by lamps stationed at wide intervals, and the shadows cast by the great building effectually concealed the form of the youth as he entered them in the course of his restless walk. It was evident that he was in a state of acute distress, and equally evident that this spot held some peculiar attraction for him, for now and again he cast a glance at the church walls, or lingered beside the closed door which was used by the members of the choir. Presently, as he was passing, the door opened, emitting a stream of yellow light across the wet pavement, and a number of youths sallied forth, talking and laughing together as they came. At the sound of the creaking hinges the destitute boy shrank back into the shadow, as if he were afraid of being recognised—which, indeed, was the case. Nevertheless, on catching a glimpse of one young face, as the figure of its owner almost brushed against him, he could not refrain from exclaiming under his breath, ‘Michael!’

So low was the tone in which the name was uttered, that, although the chorister’s face, with the light from the doorway falling upon it, was turned for a second in the speaker’s direction, the boy failed to grasp the meaning of the sound, and hurried on with his companions; and with a deep sigh the poor wanderer turned away.

At that moment a young man who was crossing the square from the opposite side paused to turn up the collar of his coat. In so doing he became aware that a pair of eyes was regarding him with a sorrowful, appealing gaze from the depths of the shadows. In another moment he had advanced to the youth’s side and laid his hand upon his shoulder.

‘Joseph! can it be you? Man, how wet you are!’ The outcast shivered under the friendly touch. ‘What are you doing? Where have you been living?’ continued the questioner, drawing the youth into the light of a lamp, and regarding his pale, tired face with astonishment.

‘Starving—you! This is Reutter’s handiwork,’ said the other angrily. ‘Have you seen your brother Michael? I met them coming out just now. Was he not with the rest?’ he added in a gentler tone, still keeping his hand on the lad’s shoulder.

‘Yes, he was there; but he didn’t see me,’ replied the wanderer hesitatingly, adding, ‘I was afraid the others might notice my distress.’

The friend bit his lip and seemed to be meditating. At last he spoke. ‘Well, see here, Joseph, we cannot stand longer in the rain; come home with me. You know I haven’t a palace to offer you, but such as it is you are welcome to a share of it for one night at least.’ And so saying he drew Joseph’s arm within his own, and, bidding him walk fast, the pair quitted the square.

Well might honest Franz Spangler, who held no higher or more lucrative post than that of tenor singer in the choir of St. Michael’s Church, warn his young friend not to expect the luxury of a home replete with comforts. Indeed, anyone comparing the two young men as they threaded the narrow streets leading to Spangler’s abode would have found it no easy matter to determine which presented the shabbier appearance; though, having decided this point to his satisfaction, he would have been at no trouble in estimating the sort of house to which the chorister would be likely to introduce his friend.

Situated in the poorest quarter of the town, the house presented a sufficiently poverty-stricken appearance to warrant the meanest opinion being entertained with regard to Spangler’s powers of hospitality. The kind-hearted singer was, in fact, almost as poor as the youth whom he had befriended, with the additional responsibility entailed by a wife and child. Nevertheless, to the homeless, starving lad who now followed his protector up the crazy stairs leading to the garret which comprised the latter’s home, the chorister seemed by comparison prosperous and well-to-do. Was it not luxury to be invited to seat himself beside the scanty fire burning in the stove, and to feel its warmth slowly penetrating to his chilled bones? Was it not luxury to one who had tramped the streets—those endless, pitiless streets—during the past eight-and-forty hours, without food or shelter, to taste the warm bread-and-milk which his kindly hostess had contrived to eke out of her small stock? Finally, was it not the height of luxury to such an one to stretch his weary limbs beside the dying embers, and sleep the sleep which exhausted nature demanded?

The heart of Spangler might well have been touched by the distress into which his young friend had fallen, seeing that he was already acquainted with some of the circumstances to which his forlorn condition was due. And life had promised so differently for poor Joseph but a short while ago! When, some four years prior to this meeting, he had welcomed the coming of his younger brother Michael to the Cantorei, or choir-school of St. Stephen’s, he could not have divined that this brother would, indirectly, be the cause of his being turned adrift into the streets. Yet such was the melancholy fact, and as to the manner in which this was brought about we may properly inquire while the subject of this history lies wrapped in slumber beside the garret stove.

About fifteen leagues to the southward of Vienna, and amidst the marshy flats bordering upon the River Leitha, lies the little village of Rohrau, which derives its name from its situation. At the extreme end of the long, straggling street which comprises the village stands, close to the river banks, a low, thatched building—half house, half cottage—with a wheelwright’s shop adjoining. The house stands back a little way from the road, with a patch of greensward before it, on which, in the days to which our story belongs, one might have seen a waggon or two in process of repair, and possibly have caught a glimpse of the worthy wheelwright himself at his work.

Mathias Haydn, master wheelwright, and sexton of the little church standing on the hill outside the village, was in the fullest sense entitled to rank as a worthy: he was not only a deeply religious man, but one who was looked up to and respected by every one in the village and for many a mile around. There was an air of refinement about his home which raised it far above the level of the homes by which it was surrounded. A strong taste for music formed a part of Mathias’s nature, and it was shared to a great extent by his wife Maria. Regularly each Sunday evening, when the duties of the day were finished, he would bring out his harp, which he had learnt to play by ear, and accompany himself in songs and hymns. He had a pleasing tenor voice, and sang with great expression. The wife also sang well, and, joining in with her husband on these occasions, their example soon induced the children to add their voices to the concert.

The long winter evenings were those specially devoted to music. It was at one of such times, when the village street was deserted, and the keen wind was sweeping it from end to end, sporting with the snow, lifting it in whirling clouds, and building up drifts at every corner; whilst away on the lonely marshes the ice-bound river lay shimmering in the frosty moonlight, and the blast soughed through the tall reeds and grasses, that the following little scene was being enacted within the kitchen of the wheelwright’s cottage.

On the oaken settle next the stove sat a child of about five years of age, following with the closest attention his father’s performance on the harp. In his hands were two sticks, with which he was imitating the playing of a violin, keeping accurate time with his bow to the rhythm of the music. The rapt expression on the boy’s face was not lost upon the father, and thoughts which more than once had occupied Mathias’s mind as he watched his child’s clever imitation of the village schoolmaster’s playing of the violin were recurring with redoubled force on this occasion. And when the boy lifted up his sweet treble voice in unison with the rest its beauty sent a thrill through the father’s heart. His own life had been a keen disappointment with respect to his passionate love for music—a love which had made him yearn to know more of the art for which he had so profound a reverence. Hence the determination that his child should have every chance that he could afford of developing such talents as he possessed gathered strength as he perceived the manifestations of delight on the part of little Joseph every time the harp was produced, and as he noted the quickness and accuracy with which the boy learnt the simple melodies that were played to him. And as time went on these thoughts kindled a hope in the father’s breast that his little Joseph might one day become a musician, and perhaps—who could tell?—he might even rise to be a Capellmeister!

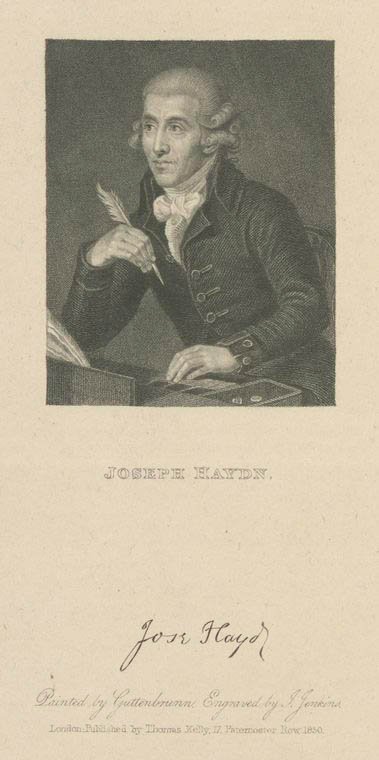

Joseph Haydn, the subject of our story and the centre of his father’s hopes, was born on March 31, 1732, and had attained his sixth year when the first step towards the settlement of his future was taken by his parents. Previous to this event Mathias had confided to his wife the hopes which he entertained with regard to Joseph’s musical career, in the expectation that she would share them. Maria, however, did not incline to her husband’s views on the subject. She cherished a strong desire that Joseph should eventually join the priesthood, and fancied that she detected in the boy’s reverence for sacred music a natural leaning in that direction.

Matters were at this juncture when an unexpected visit was paid to the cottage by a distant relative named Johann Mathias Frankh, the schoolmaster of Hainburg, a small town about four leagues from Rohrau. Frankh, who was himself a fair musician, happened to visit the family at the moment when they were engaged in their evening concert, and the sight of Joseph with his toy violin at once attracted his attention. The purity and accuracy of the child’s singing, moreover, soon convinced the schoolmaster that he had in him the makings of a good musician, and without knowing anything of the parents’ wishes or intentions, he immediately proposed that Joseph should be placed under his instruction. ‘If you will let Sepperl (the Austrian diminutive for Joseph) come to me,’ said he, ‘I will take care that he is properly taught. I can see that he promises well.’

Mathias gave a willing consent to the proposition, and Maria’s objections having been overruled (she kept to herself the hope that this might, after all, prove to be but a stepping-stone to the fulfilment of her wishes), in a very short time Joseph and his father were seated in the waggon and jogging on their way to Hainburg.

The new world into which Joseph found himself launched had many drawbacks, but one excellent side. His ‘cousin,’ as he termed Frankh, was a strict but careful teacher, and under his care the boy not only learned to sing well, but also acquired a good deal of knowledge regarding the various musical instruments in use at that time. In other respects, too, his education was looked after; and as his quickness at learning was remarkable, and his cousin did not scruple to employ physical force to enable his pupil to master his difficulties, Joseph made rapid progress, despite the fact that he was often flogged when he should have been fed. The strict discipline to which he was subjected may not have been without its value in inducing habits of method and order in the boy’s studies; but in many ways his life was rendered unnecessarily hard. The schoolmaster was a married man, but his wife showed the utmost indifference towards the little fellow who had hoped to find in her a second mother, but who found instead that he was neglected in every way. Next to religion itself, Mathias and Maria had instilled into their children a positive reverence for personal cleanliness. Joseph’s distress, therefore, at finding himself bereft of a mother’s care became greater day by day as he saw the rents in his clothing passed over and the means of keeping his body in the state to which he had been accustomed unprovided. What this meant to a sensitive child with a rooted aversion to dirt may be imagined; nor were his sufferings in any way reduced by the attention which his destitute, neglected state drew upon him. Try as he might to forget his misery in his books, he could not but be aware of the pitying glances which were cast at him by those whom he encountered in his walks, or who passed by as he sat reading on the step outside his cousin’s door.

Though ashamed of his appearance, Joseph was in no danger of losing his self-respect—the love of cleanliness and order had been too deeply implanted to be easily uprooted; moreover, his childish reason whispered to him that the present state of things could not last for ever, and in the meantime he bravely resolved to make the best of it. He was receiving lessons on the clavier and violin, but the training of his voice occupied the foremost place, and when not in school the boy was nearly always to be found in the church, listening to the organ or the singing. In a very short time he had made such progress as to be admitted to the choir, where he joined his sweet young voice in the singing of the Masses.

Already his mind was beginning to feed upon those higher branches of music which his natural gifts enabled him to appreciate. His reverential nature was strongly shown in regard to his music, and it was in the church alone that he could obtain the gratification of a sense which was surely leading him on to greater things. As the days went by he was conscious of a yearning for something that his present surroundings could not supply. His thoughts were constantly travelling towards a city wherein he had centred his hopes, and where he knew he should find his heart’s desires. That city was Vienna. It was before his eyes as he stood in the choir of Hainburg Church; it came between him and his book as he sat in the schoolroom conning his lesson; it was in his dreams as he slept, as it was foremost in his thoughts on waking. But Vienna lay afar off; and looking down at his ragged clothing, and reflecting upon the poverty that surrounded him, Joseph wondered if it would ever be possible for him to realise his dream.

‘Sepperl, come here; I want you.’ It was his cousin Frankh’s voice, calling to him as he was leaving the schoolroom one morning. ‘There is to be a procession through the town next week, in honour of a respected citizen who died yesterday. They have asked me to supply a drummer, and I thought of you at once. Come, I will show you how to make the stroke,’ and, taking Joseph by the hand, he led him into the yard where, having improvised a drum by turning a tub bottom uppermost, Frankh placed a stick in the boy’s hand and bade him beat the time of a march. A few attempts sufficed to convince Frankh of his pupil’s proficiency, and Joseph was duly installed in the drummer’s place. Owing, however, to his small stature, it was found necessary to call in the help of a schoolboy of his own height, and as this boy happened to be a hunchback, he was enabled to carry the drums on his back at the proper level for Joseph to beat them. The comical effect thus produced proved too much for the gravity of many of the bystanders, but Joseph went through his business with solemnity, secretly deriving much pleasure from this public exhibition of his skill, and thereafter he always retained an affection for the instrument as well as a knowledge of how it should be played.

Haydn had just completed the second year of his school life at Hainburg, when an event happened which brought the realisation of his dreams suddenly within his grasp. The Capellmeister of St. Stephen’s Cathedral, in Vienna, George Reutter, was paying a visit to his friend, the pastor of Hainburg, and in the course of conversation he mentioned that he was in want of some good voices for the cathedral choir. ‘Then I think I can find you one at least,’ replied his friend; ‘he is a scholar of Frankh’s, the schoolmaster here, and possesses an excellent voice. Shall we send for him?’ Reutter agreed, and a message was accordingly dispatched to Frankh.

In due course the schoolmaster appeared, leading Haydn by the hand, and the pair were ushered into the presence of Reutter.

The Capellmeister eyed the boy kindly, and, drawing him to his knee, said, ‘Well, my little fellow, can you make a shake?’

Joseph looked up brightly. ‘No, sir; but, then, no more can my cousin Frankh here.’

Reutter laughed at this outspokenness, and then, telling Haydn to attend to him, he proceeded to show him how the shake was to be performed. After a few attempts Joseph succeeded in satisfying his instructor, who praised him for his quickness. During the experiment the boy’s eyes had been fixed on a dish of cherries standing on the pastor’s table. Reutter, perceiving the longing thus silently expressed, reached out his hand for the dish, and telling Joseph that he had earned his reward, he emptied the contents into the boy’s pockets.

Haydn was next requested to sing a portion of a Mass which he knew by heart, and when this trial was finished the Capellmeister expressed his willingness to take him into the Cantorei of St. Stephen’s.

The boy’s heart leapt within him as he heard the words. It was so unexpected; it seemed almost too good to be true! Then suddenly the thought of his ragged clothing swept across his mind, and the tears started to his eyes. Surely, they would never admit such an urchin as he to the famous choir-school! Reutter, however, did not seem to heed his untidy state, and Haydn took heart of hope that after all this might be remedied. In the letter which he wrote to his parents, asking for their consent, he included an appeal for money wherewith to purchase new clothing. Mathias had a large family to support on his slender earnings, but he contrived to send a few florins for the purpose, and as both parents at the same time gave a willing assent to his leaving Hainburg, Joseph felt that every obstacle to the fulfilment of his happiness had now been removed. The parting with his teacher, however, was not accomplished without some regrets, for, after all, Frankh, despite his severity, had done well by his pupil, and that pupil was not slow in expressing his gratitude for all that he owed to his relative’s instruction.

Possibly, if Joseph could have looked across the leagues which lay between him and the city to which he was journeying with a power of prophetic vision that enabled him to realise a portion of the future that awaited him, he might have experienced some degree of misgiving. But, happily for him, no cloud arose to obscure the sunny picture which his imagination had drawn of the life that was opening before him. Roseate, indeed, were the hues in which his fancy had painted that picture, and foremost of all the objects that it contained was the famous cathedral, with its magnificent spire pointing into the clouds, its richly-sculptured stones, its glorious nave, flanked by noble pillars, and its lofty vaulted roof, echoing to the voices of the choir, or reverberating to the notes of the organ, the whole flooded by the soft light falling from the painted windows. To picture all this from the descriptions which had been given to him was to conjure up a vision of indescribable beauty. And then, the Cantorei itself—had not his cousin Frankh assured him that he would be taught singing and to play the clavier and violin by the best masters, in addition to Latin, writing, and cyphering? Lastly, there was the life which went on outside the cathedral and the choir-school—the life of a city within whose walls music had established a home, wherein she flourished as nowhere else in the wide world could she be said to flourish.

All this, and more, had the eight-year-old musician learnt from conversation and report during his two years’ sojourn at Hainburg; and of all this was he thinking as he travelled to Vienna with a heart and mind yearning to enter into the joys and labours of such an existence.

With what fervour he embarked upon his studies at the Cantorei, as well as how quickly he progressed under the care of his teachers, may be imagined. Child though he was, nothing in the shape of learning came hard to him, and difficulties seemed to be created only in order to be successfully overcome. Very soon came the desire to compose; but just here the toughest obstacle of all, perhaps, presented itself—the studies comprised no instruction in counterpoint. Still, Joseph was not to be daunted. Seizing upon every scrap of music-paper that he could find, he covered it with notes. ‘If only the paper is nice and full, it must be right,’ he said to himself, as he bent his energies to the task.

Reutter, however, gave him no encouragement to proceed in this direction. ‘What are you about, Haydn?’ inquired the Capellmeister one day, as he lighted upon the boy suddenly in the midst of a composition. Joseph looked up with a flush mantling in his cheeks. ‘I am composing, sir,’ he answered. ‘Let me see it,’ requested the master. It was a sketch of a ‘Salve Regina’ for twelve voices. Reutter glanced at the work, and then tossed it back. ‘Why don’t you try to write it for two voices before attempting it in twelve?’ was his only comment, uttered in a sharp tone, in which sarcasm was too plainly apparent. Joseph blushed deeper than before. ‘Oh,’ he said simply; it was all he could say, for the master’s sneer had struck home. ‘And if you must try your hand at composition,’ continued Reutter in a somewhat kinder tone than before, as he observed the tears spring to the boy’s eyes, ‘let me advise you to write variations on the motets and vespers which are played in the church.’ With this parting piece of counsel he passed on, leaving poor Haydn as much in the dark as before with regard to how he ought to proceed. ‘If only he would instruct me in counterpoint, how I would thank him!’ was the thought uppermost in Joseph’s mind, as he put his despised work out of sight.

But no instruction in the art of composition was forthcoming from either the Capellmeister or any of the teachers, and Haydn was thrown back upon his own resources. He possessed the talent, however, as well as the perseverance, and of neither of these qualifications could they dispossess him, and so, taking to heart Reutter’s well-meant admonition, he set to work afresh. His resources in the shape of pocket-money were almost nil, yet by dint of scraping and denying himself he managed to save sufficient to purchase two volumes, upon the outsides of which his eyes had often feasted as the books lay temptingly displayed upon the shelf of the second-hand bookseller. One of these works was Fux’s ‘Gradus ad Parnassum’ (a treatise on composition and counterpoint), and the other Mattheson’s ‘Vollkommene Capellmeister’ (the Complete Chapel-master).

But no instruction in the art of composition was forthcoming from either the Capellmeister or any of the teachers, and Haydn was thrown back upon his own resources. He possessed the talent, however, as well as the perseverance, and of neither of these qualifications could they dispossess him, and so, taking to heart Reutter’s well-meant admonition, he set to work afresh. His resources in the shape of pocket-money were almost nil, yet by dint of scraping and denying himself he managed to save sufficient to purchase two volumes, upon the outsides of which his eyes had often feasted as the books lay temptingly displayed upon the shelf of the second-hand bookseller. One of these works was Fux’s ‘Gradus ad Parnassum’ (a treatise on composition and counterpoint), and the other Mattheson’s ‘Vollkommene Capellmeister’ (the Complete Chapel-master).

Precious indeed were these hardly-acquired volumes. Every moment that could be snatched from schoolwork or choir-practice was devoted to mastering the difficulties of the ‘Gradus,’ and in acquiring knowledge concerning the high office which he had secretly set his heart upon obtaining. There was unconscious humour in the fact that, following upon Reutter’s reproof to his over-ambitious strivings, the chorister should have set himself to study the duties of his master’s post. Yet the temptation to smile is checked by the thought of the lonely student giving up his play-hours to self-imposed study, battling in grim earnest with problems that might well have turned the edge of a determination less keen than that which was set to conquer them, and battling thus unassisted and often, no doubt, against the craving for food and fresh air which is inseparable from boyhood.

It would be wrong, however, to suppose that Haydn absented himself wholly from his companions and their merry games. There was within him a soul for play as well as for work, and there were occasions when the spirit of mischief obtained the ascendancy. The choir was frequently required to perform in the Royal Chapel when the Court was in residence at Schönbrunn. The palace there had been newly erected, and the workmen had not removed the scaffolding, a fact which was hailed with delight by the choir-boys as affording an unlooked-for means of relaxation. One after another climbed the poles, each striving to outdo the rest in attaining the highest point. In vain did the Empress Maria Theresa, who had perceived them from her windows, issue prohibitions and threaten dire punishment to the offenders—the sport went on unchecked. At length a moment arrived when Joseph, who had beaten his companions by climbing to the top of the tallest pole, and was daring them to come up to him, was detected by the Empress in the very act. The Hofcompositor was sent for, and the figure of Haydn rocking himself to and fro on the pole duly pointed out. ‘Give that fair-haired blockhead einen recenten Schilling’ (slang for a ‘good hiding’); ‘he is the ringleader of them all,’ said the Empress. The descent of Joseph from his elevated perch, and the descent of the Hofcompositor’s rod, were events which speedily followed the royal command.

A love of fun formed an essential part of Haydn’s nature, but music came before anything else. Even when playing with his fellow-choristers in the cathedral square he would break away from the game at the first sound of the organ, and enter the church to listen. His desire to perfect himself in music was so strong that to the ordinary hours of study and practice he voluntarily added several more each day, with the result that he was often working sixteen or eighteen hours out of the twenty-four.

Five years had passed amidst these happy surroundings when Haydn awoke one morning with the joyous thought that that day was to witness the arrival of his younger brother Michael at the Cantorei. How eagerly he had looked forward to this break in his life, with what zeal he had planned how he was to assist Michael in his work, when he had smoothed the young one’s entry, helped him over his shyness, and shown him all the delightful scenes and circumstances which his new life would comprise. It had infused new vigour into his resolutions, and fired him with fresh ardour for his own work, this coming of his brother to share with him the pleasures which he had possessed for so long alone.

Joseph’s unselfish and generous feelings may have helped to blind his vision to the little cloud which, almost from the moment when Michael’s pure young treble notes first soared aloft into the cathedral’s vast recesses, had begun to shut out some of the sunshine that had gladdened his own existence. Certain it is that he had no inkling of the sorrow which his brother’s advent was destined to bring upon him. Michael’s progress was remarkably rapid, and it was soon apparent that Joseph’s prospects were as surely declining. The voice which hitherto had enabled him to hold the chief place in the choir showed signs of breaking, and one after another of the solo parts which formerly he alone had been selected to sing were assigned to the new chorister. Joseph’s failing powers were unmistakably betrayed when he sang before the Court, and, though intended only as a joke, the Empress’s remark to Reutter that Haydn’s singing had come to resemble the crowing of a cock, sufficed to open the Capellmeister’s eyes to the fact that Joseph must be put back. Consequently, at the celebration of St. Leopold in the presence of the Emperor and Empress, the singing of the ‘Salve Regina’ fell to the lot of Michael, whose rendering so entranced his royal hearers that they presented the young chorister with a sum of twenty ducats.

To no one could it have been plainer than to poor Joseph himself that the sun of his glory at St. Stephen’s had set never to rise again. His place was now virtually taken by the brother whose coming he had welcomed, and the royal favours which heretofore had been allotted to him were transferred to Michael for good. Mortified as he must have felt at the slight thus accorded to him, Haydn cherished no feelings of resentment towards the brother by whom he had been supplanted. He had the good sense to attribute his misfortune to his failing voice alone and to fall back upon the belief in his own powers to make his way as a musician, which formed his one unfailing resource and comfort during those darkening hours.

How long Haydn might have remained at the Cantorei, in spite of his breaking voice, and the consequent lessening of his importance as a member of the choir, cannot be told; but an incident which happened at this period settled his future as far as St. Stephen’s was concerned, in a manner as summary as it was unexpected.

It is odd that Haydn’s actual dismissal from the school must be laid at the door of his love of fun, and that one who was so hard-working and so wrapped up in his music should have been unable to resist the temptation to play off a practical joke upon one of his colleagues under the very eyes of the Capellmeister. Nevertheless, such was the case, and a bright new pair of scissors, which had found their way into his possession, was the means by which Joseph executed his joke, and at the same time severed his connection with the Cantorei. It was the fashion in those days for boys to wear pigtails, and Haydn’s gaze was one day riveted upon the movements of a pigtail belonging to the chorister seated immediately in front of him. The pigtail was twitched to and fro, or jerked up and down, in accordance with the movements of its owner’s head, with a vivacity which was at once fascinating and exasperating to behold. The new scissors were being opened and closed in Joseph’s fingers—the itching to cut something was too strong to be resisted—the tantalising pigtail was twitching under his very nose—and the next moment, ere the owner of the scissors could realise the crime he was committing, the once active pigtail lay as dead as any doornail upon the floor.

The punishment meted out to Haydn for this offence was slight—a mere caning on the hand; but the indignity and disgrace of being caned before the whole school was not to be borne. He pleaded for forgiveness: ‘Rather than submit to such a disgrace he would leave the school.’ Reutter had for long been seeking an excuse for turning the lad adrift; a chorister without a voice was useless to him, and here was his chance. ‘You must take your caning first, and then you shall have your dismissal,’ he said, with cruel meaning in his tone, for he knew Haydn’s spirit.

Joseph underwent the disgrace, and then, whilst the physical pain of it yet lingered, he packed up his two precious volumes, placed the remainder of his belongings on his brother’s bed, and choking back the rage that was almost suffocating him, he walked quickly out of the building into the street.

Having thus related the manner in which our hero was launched upon the sea of adversity, without means of subsistence, and with no better companion in his misery than the wrath aroused by the sense of his harsh and unjust treatment, we must return to the point at which we left him stretched beside the stove in Spangler’s garret. At the same time we desire to correct an impression which the reader may have formed from the opening portion of our story that, at the moment of his chancing upon this friend in need, Joseph was longing to return to the comfortable quarters which he had quitted in such fiery haste. Such an impression would be far from representing the true state of Haydn’s feelings at the time. He had, indeed, hoped to encounter Michael—to speak a word with him, to beg of him, in fact, a crust of bread; but his heart failed him when he saw his brother amongst his companions, and pride stepped in as well to prevent him from exposing his distress to so many curious eyes. Thus far he had yielded to the promptings of hunger, but his resolution not to re-enter the school had stood firm, in spite of the cravings of nature, in spite of his friendless position, in spite of the long dreary vista of want which the past eight-and-forty hours had opened to his eyes. He had acted upon the impulse of the moment, but the bitterness of the cause which prompted that action remained—nay, more, it was already acting like a tonic upon a nature disciplined to look difficulties bravely in the face. Those few hours of sound sleep put new life into his frame, and when he awoke it was with the resolve to refrain from any further attempt to see his brother, lest his desperate condition should unsettle the younger one and render him unhappy. It would be a hard, uphill fight, but he would fight it alone—not even his parents should hear of him again unless he succeeded.

‘Now, Joseph, what do you propose to do?’ was the inquiry of his host, when the morning fast had been broken by a porringer of bread-and-milk. ‘Have you made up your mind to go back to the school? or will you send word to your people that you intend to return home?’

‘I will never go back to the school,’ answered Joseph firmly, ‘and as for going home, that is even further from my intentions than the other.’ And then he told his friend of the poverty which reigned at home in consequence of the large and growing family, and the disgrace which he should feel in casting himself as a burden upon those he loved, especially after what had occurred. ‘Sooner than do that,’ he exclaimed, ‘I would rather starve in the streets. But, indeed, I believe it will not be so bad as that; I have made up my mind to support myself by music, and I will never give in!‘

Now Spangler, albeit a man of humble attainments, and a being, moreover, who had set no very high ideals before his eyes, was not, as we have seen, destitute of the quality of sympathy, nor could he entirely obliterate from his memory a time when he himself had been fired by a spark of ambition, and had recognised a longing to accomplish something great. True, the spark had been but a feeble one at best, and the unceasing demands upon his powers to supply the bare necessaries of life, occasioned by an early and imprudent marriage, had done their best to crush it out of existence. Nevertheless, the memory of that time remained, and being freshly stirred by the contemplation of his young friend’s forlorn state, it united itself with the stronger germ of sympathy, and blossomed out into a generous proposal that Haydn should continue to occupy a corner of his garret until such time as he could obtain employment.

Haydn gratefully accepted the kindly offer, assuring Spangler that he would repay his hospitality both in money and thanks. He gave this assurance in the belief that its fulfilment could only be a question of a short time. But many weary months, spent in fruitless applications for employment and equally futile endeavours to secure pupils, were destined to pass ere the first vestiges of success made themselves apparent. Haydn was now seventeen, and possessed of the appetite of a schoolboy; how to satisfy his natural cravings, therefore, must have been almost as difficult a problem as that of obtaining work. The rigours of an Austrian winter, too, added not a little to his miseries, ill-fed and thinly clad as he was, but still he struggled on, hopeful that the advent of spring would bring good luck with the sunshine.

Spring came at last, and found him still without means of subsistence, yet not without the solace of hope. Notwithstanding the uncongeniality of his surroundings, he had found opportunities for study, and never had his treasured volumes seemed more precious to him than during those long winter months, when despair haunted him like a shadow from which there seemed no means of escape. His sole earnings had been the pence flung to him from the windows as he stood singing in the snow-covered streets, either alone or in the company of other youths as destitute as himself. But now spring had come; the glorious sun had chased away the snow and the biting frost, and the poor chorister felt its genial rays quickening the life-blood in his veins, and awakening his cramped muscles to action. It is only the pinched and starved human beings of this great Northern Hemisphere who really know what a beneficent food-giver is the sun.

One morning, as Haydn stood idly wondering what he should do next, a procession of men and women, headed by several priests, passed by, bound for the shrine of the Virgin at Mariazell. Struck with an idea, Haydn joined the cavalcade, and on reaching the church in which the pilgrims were to assemble, he sought out the choirmaster, and, telling him how and where he had been trained, begged for employment. With a contemptuous glance at the ex-chorister’s ragged clothing, however, the master bade him begone, saying ‘that he had had enough of lazy rascals such as he coming from Vienna to seek for work.’ The tears started to the lad’s eyes as he turned away. Would nobody hold out a helping hand? He had been speculating upon this opportunity as he trudged along the road until it seemed almost a certainty; and must this cup, too, be dashed from his lips?

A few minutes later he perceived the choristers entering the church by a side-door, and, emboldened by hunger, he slipped in amongst them, donned a surplice, and took his place in the stalls. Finding himself next to the principal soloist, he requested that he might be allowed to share the latter’s copy. The request was indignantly refused, but Haydn, who knew the service almost by heart, resolved to await his opportunity. When the moment arrived for the singing of the solo, he snatched the copy from the chorister’s hands, and, lifting up his voice, sang the part with such exquisite finish and beauty of expression as to electrify the rest of the choir and excite the admiration of the master.

At the conclusion of the service Haydn was sent for by the choirmaster, who, after expressing his regret for his former abruptness, asked him to stay with them until the following day. Poor starving Haydn was only too glad to accept the invitation, and when the morrow arrived he was told that he might extend his stay for several days longer. When, therefore, he finally returned to Vienna, it was with a small sum of money jingling in his pockets and a frame invigorated by a liberal supply of such food as it had not been his privilege to taste since the day when he quitted the Cantorei of St. Stephen’s.

It was the first gleam of sunshine that had crossed his path since those happy days, and it served to dispel some of the gloomy desperation which, during the long, dark days of winter, had laid constant siege to his resolutions, which had, indeed, once or twice nearly shaken them from that bed-rock of belief in his own unaided powers which, coupled with his simple faith in God, had sustained him and sent him forward from day to day. Often had he lain, shivering and famished, beneath his scanty coverlet in the corner of the garret allotted to him, watching the stars shining through the skylight above his head, and praying, with all the earnestness of a warrior-knight of the Middle Ages, for strength to battle with the temptation of despair. If music—the music that raises and ennobles, that strengthens, and uplifts the soul of man to heights which bring him nearer and ever nearer to a true conception of God—were destined to find a voice in Haydn’s soul, that music must have owed its inception to those midnight hours of silent communion—those struggles with natural want—which were passed beneath the rafters of his miserable lodging.

And gradually his determination prevailed. The tide of fortune sent some ripples of success to his feet. A few pupils were induced by the trifling charge which he made to let him give them lessons on the clavier; a like desire for economy probably induced others to employ his services occasionally as violin-player at balls and other entertainments; whilst one or two aspirants for musical honours permitted him to undertake the revision and arrangement of their compositions at a small fee. Such cheering signs of improved prospects, feeble in themselves, assumed in Haydn’s eyes the aspect of rewards for which he could not be sufficiently grateful.

And then the tide of success came with something like a rush. A worthy tradesman, named Buchholz, who loved music, and had occasionally invited Haydn to sing and play to him after business hours, was touched by his distress, and as a proof of his faith in the struggling musician’s honour, as well as with a desire to help him on his way, he lent him the sum of a hundred and fifty florins, to be repaid, without interest, when opportunity permitted.

To Haydn such a sum seemed a veritable fortune, and, indeed, it brought with it the power of effecting great changes in his life. He was now enabled to quit the tenement of Spangler and take a garret of his own, or what was, in truth, a portion partitioned off from a larger garret. As an exchange the new abode was not without its drawbacks. Semi-darkness prevailed even at midday; there was no stove, and as the summer had come and gone and winter was once more upon the city its discomforts were speedily made manifest by the rain and snow, which found their way through the broken roof. Nor were his neighbours in the least inclined to respect his desire for quietude. Nevertheless, in spite of these hardships, Haydn was happy—’too happy,’ as he himself put it, ‘to envy the lot of Kings’; for had he not added to his priceless treasures the first six sonatas of Emmanuel Bach, which he lost no time in mastering? More than this, he had become the possessor of a little clavier—a poor, worm-eaten instrument, it is true, but one which brought much solace to him in his loneliness.

On the third story of the house in which Haydn was living lodged an Italian poet of some celebrity—Metastasio by name—between whom and the friendless ex-chorister an acquaintance sprang up which resulted in Haydn’s introduction as music-teacher to the poet’s favourite pupil, Marianne Martinez. Upon the heels of this piece of good fortune followed a second. Through Metastasio’s interest Haydn became acquainted with Nicolo Porpora, the most eminent teacher of singing and composition of his day, who was at the time giving singing-lessons to Marianne. But before sufficient time had elapsed for the latter introduction to produce any definite result, Haydn had found employment in a new and unlooked-for direction.

It was a common fashion in Vienna at that day for poor and struggling musicians to earn a few florins by serenading personages of note in the town; but as the number of would-be serenaders was always far in excess of the number of celebrities who aspired to be thus honoured, the pecuniary advantages, as a rule, were very small. It happened, however, that Felix Kurz, the manager of one of the principal Viennese theatres, had lately married a beautiful woman, whose charms were the theme of conversation in fashionable circles, and it occurred to Haydn and two of his companions to serenade the lady with music of the former’s own composing. Accordingly, the trio repaired one night to Madame Kurz’s windows and began their performance. Presently the door opened, and the figure of Kurz appeared, enfolded in a dressing-gown. Beckoning to Haydn, he inquired, ‘Whose music is that which you were playing just now?’ ‘My own,’ replied the serenader. ‘Indeed!’ responded Kurz, opening his eyes in surprise. ‘Then just step inside, if you please,’ Haydn obeyed wonderingly, and having been first introduced to madame, who complimented him on his performance, he was conducted by the manager to the parlour, where refreshments were produced for himself and his companions. ‘Come and see me to-morrow,’ said Kurz to Haydn at parting. ‘I think I have some work for you.’

When Haydn put in an appearance on the following day the manager at once proceeded to business. He explained that he had just written a comic opera, to which he had given the title of ‘The Devil on Two Sticks,’ and was looking out for a musician to set it to music. He had been struck by Haydn’s serenade on the previous night, and believed that he would do. ‘Now,’ he continued, ‘there is a tempest scene at sea for which appropriate music is needed. Let me hear what you would suggest.’

Haydn seated himself at the harpsichord, but as he had never seen the sea in his life, he felt at a loss how to begin. After trying a few chords he mentioned his difficulty to Kurz. ‘Oh, I haven’t seen it, either,’ responded the manager airily; ‘but I imagine it is something like this’—and he began to throw his arms into the air as he paced up and down. ‘Picture a mountain rising, then a valley sinking; then a second mountain, and another valley—mountains and abysses following one another—there you are!’

In vain Haydn grappled with the subject—trying it in fifths, in fourths, then in octaves—the excited manager meanwhile tossing his arms about, and shouting and gesticulating. It was all to no purpose. At length, losing all patience, Haydn cried, ‘The devil take the tempest!’ at the same moment plumping his hands with a crash on to the extreme ends of the keyboard, and then rapidly bringing them together. ‘That’s it, that’s it! You’ve got it now!’ cried the delighted Kurz, springing at the astonished composer and embracing him with fervour.

From that moment all went well, and the opera was completed to the author’s satisfaction, albeit Haydn, glad as he was to receive his reward, felt that he had little cause for self-congratulation at the results from a musicianly point of view. The opera was duly produced, and received with some measure of approval; but its life was no longer than its merits deserved, and Haydn himself was not desirous of delaying its interment, for he had higher work in view.

We must now return to his acquaintanceship with Porpora. The singing-master had observed Haydn’s skill in playing the harpsichord, and thinking that he saw his way to turning the poor musician’s abilities to a useful purpose, he offered to employ him as accompanist. Haydn gladly accepted the proposal, hoping that he would thus be enabled to pick up something of the master’s method. Though ostensibly engaged to play the accompaniments of Porpora’s songs when the latter was giving his pupils their lessons, Joseph soon found that he was regarded in no higher light than that of an ordinary serving-man. The discovery of this fact, however, occasioned him no dismay, nor did he exhibit the slightest repugnance at being called upon to clean his master’s shoes, brush his coat, or dress his periwig. In vain did the sour old man hurl such epithets as ‘fool,’ ‘blockhead,’ ‘dolt,’ at his musical valet in return for the latter’s attempts to minister to his personal comforts. Haydn’s sole object was to be near Porpora in order that he might garner each crumb of knowledge—each hint, however small—that the great man chanced to let fall from his stores of learning; and the master, noting his perseverance and also the gentleness with which he took his buffetings and sarcasms, gradually softened towards his dependent, and, beginning by giving him a stray piece of advice now and then, ended by answering all his questions, and setting him right where he needed correction in his compositions. To crown all, Porpora brought Haydn under the notice of the nobleman in whose house he was teaching, with the result that, when the nobleman took his family to the baths of Mannersdorf for several months, Haydn, to his delight, was allowed to accompany the party in the capacity of Porpora’s accompanist.

This piece of good fortune proved to be the turning-point in his career, for the eminent musicians whom he met at Mannersdorf not only received him very kindly, but evinced the greatest interest in his compositions, many of which were performed during this visit. His acquaintance with one of these musicians—a well-known violinist named Dittersdorf—ripened into friendship, and led to Haydn’s receiving violin lessons at this master’s hands. Another solid advantage accruing from his association with Porpora lay in the fact that the nobleman himself, struck by Haydn’s progress, and desirous of helping on one who showed so great a talent for art, allotted him a pension of six sequins (£3) a month. Haydn’s action on receiving the first instalment of this generous bounty was consistent with his desire to maintain a neat appearance, as well as an indication of the distress which his privations had hitherto caused him to suffer: he instantly repaired to the nearest tailor’s and purchased a suit of black.

On his return to Vienna fortune continued to smile upon him, as if anxious to atone for her neglect in the past. One after another sought his aid in teaching and composing, with the result that he was enabled to raise his terms and move into decent lodgings. His struggles, if not actually ended, had become so lightened as to leave his mind free to pursue the higher walks of his art in comparative peace. From another quarter, too, the hand of friendship was extended to him. He received a summons to present himself at the house of the Countess Thun, whose devotion to music was only equalled by her generous patronage of those in whom she discerned the signs of genius. The Countess had lately heard one of Haydn’s clavier sonatas performed, manuscript copies of which had, in accordance with the custom prevailing amongst unknown composers, been sent to the houses of the aristocracy, and, being charmed with the beauty of the work, she had inquired the name of the composer, with the object of engaging his services.

It is probable that the Countess had formed a very different conception of Haydn’s appearance from his work, for she could scarcely conceal her surprise when he was ushered into her presence. That one so ill-dressed and—it must be confessed—so uncouth of manner could be the composer of such charming music seemed impossible. Her face showed this so plainly that Haydn, knowing her generous character, ventured to relate the story of his struggles. As he proceeded with his simple narrative, the Countess’s eyes filled with tears. She was one of the noblest of women, and her heart was touched by the reflection that the art which she loved should demand so much sacrifice and suffering from those whose lives were wholly given up to its ennoblement. She had supposed that one who could write such music must have the command of money and the influence of wealthy patrons—yet how different were the facts! Haydn’s relation ended, the Countess assured him that thenceforth he might count upon her as his friend and well-wisher as well as pupil, and the happy young musician, having attempted to express his thanks, withdrew with a heart overflowing with gratitude.

A future bright with promise had now dawned for Haydn. His works were to be heard in the best musical circles of Vienna, and praise and encouragement flowed in from every quarter. A wealthy music patron, Karl von Fürnberg, who had recognised his genius, persuaded him to compose his first quartet, and thus turned his attention to the branch of composition in which he was later on to excel. At the instance of this patron Haydn, in 1759, received the appointment of music-director to a rich Bohemian nobleman named Count Ferdinand Morzin, who was an ardent lover of music, and maintained a small orchestra at his country seat. This was a great step in his advancement, and the year which witnessed it is also memorable as having been that in which he composed his first symphony.

Haydn was now twenty-six, and no longer an unknown musician. One point with regard to his compositions had already struck many whose judgment carried weight, and had aroused some criticism on the part of the connoisseurs: this point was their originality. He appeared to have marked out for himself an independent line of work, and to be following it up with a boldness that, in the eyes of certain of his critics, savoured of an open defiance of established rules. But the fact was overlooked by these critics that the circumstances of Haydn’s life had thrown him back upon himself and compelled him to be original. His knowledge of counterpoint, to the rules of which he showed a seeming disregard, had been derived almost entirely from self-study. Without a single helping hand to guide him, he had mastered the formidable difficulties of his ‘Gradus’; and lighted only by his inborn genius, he had deliberately chosen the path which he felt to be that which would conduct him to the highest levels of his art. The independence thus gained—and which speedily showed itself in all that he wrote—was a possession born of suffering and solitude, though never of ignorance, and as such it represented the truest as well as the freest expression of his musical soul. With the dawn of brighter days he had procured and studied all the works on theory that were to be obtained, only to find himself strengthened in his determination to adhere to the line which those hours of lonely study and reflection had shown him to be the right one for him to adopt. Few, indeed, of those who had risen to be masters in music could claim to have been less influenced by the composers of their own or a previous day than could Joseph Haydn; and the progress of our story will show in what manner opportunity favoured the further growth and development of that independence which even at the present stage had impressed its stamp upon his works.

We must first of all, however, relate what befell our hero in a very different sphere from that in which we have hitherto followed his fortunes.

Some time before the period at which our story has arrived, Haydn had been engaged to teach the harpsichord to the two daughters of a wig-maker named Keller. As the lessons progressed the teacher became conscious of a growing attachment for the younger of his pupils. There was something spiritual about the character of this maiden which appealed strongly to his musical temperament, though probably the loneliness of his life at the time may have added force to his longing to possess her for his wife. His poverty, however, must have convinced him of the hopelessness of declaring himself at the moment, and for some time his love remained as a cherished secret, fed by the hope which formed almost his sole resource. But now that fortune had smiled upon him he ventured to press his cause with assurance—albeit it must be confessed that this assurance rested on no more secure basis than a salary of some twenty pounds a year and the prospect of an extended teaching connection. But his hopes were doomed to disappointment, for the maiden had in the meantime elected to take the veil, prompted so to do, most probably, by the very same leanings which had rendered her nature so attractive to poor Haydn.

Could he but have been content to bear with his disappointment, seeking in his art the consolation which she had it in her power to bestow, Haydn would have been saved much unhappiness in the future. Most likely he would have adopted this course in the end, had his will and his self-regard been stronger; but neither, it seems, was proof against the blandishments of the match-making perruquier. Anxious to secure an alliance with one who showed so much promise, Keller brought all his powers of persuasion to bear in favour of Haydn’s accepting the hand of his eldest daughter, and, sad to relate, he succeeded. Maria Anna was not only three years older than the man who pledged his faith to her before the altar of St. Stephen’s, but she comprised in her nature as much of the quality of the virago as her younger sister had exhibited of the angel. She was heartless and extravagant, prone to outbursts of uncontrollable temper, and in every way utterly unfitted to be the wife of a man whose fame had yet to be compassed. Indeed, she soon showed that she had not the slightest reverence either for her husband or his art; for all she cared, Haydn might just as well have been a cobbler as an artist, provided he supplied her with money to satisfy her extravagant desires.

Fortunately for Haydn, the circumstances of his life were about to undergo an important change. Count Morzin was compelled to reduce his establishment, and hence dismissed his band and its director. What might otherwise have proved a great misfortune for Haydn was, however, the means of securing for him a post which not only raised him to the position which he had set his heart on attaining, but precluded the possibility of his wife’s living with him. Amongst those who had visited Count Morzin’s house and listened with delight to the performance of Haydn’s compositions was the then reigning Prince of Hungary, Paul Anton Esterhazy. No sooner had the Prince been made aware of Count Morzin’s intentions than he offered Haydn the post of second Capellmeister at his country seat of Eisenstadt. The chief Capellmeister, whose name was Werner, was old and infirm, but the Prince retained him in his position on account of his length of service. To Haydn, however, was assigned the sole control of the orchestra, as well as a free hand in regard to most of the musical arrangements.

It is needless to recount the joyful feelings with which Haydn received the news of his appointment, offering as it did the most exceptional opportunities for prosecuting his beloved art. Not even in his wildest dreams could he have pictured such magnificence as that which greeted him on his arrival at the Palace of Eisenstadt. For generations past the Esterhazys had been devotedly attached to music, and the reigning Prince had spared neither pains nor expense to equip his establishment with the means of performing not only the fullest Church services, but complete operas as well. The sight of the huge building, with its spacious halls and apartments and its troops of servants; the enchanting grounds, decked with parterres of choicest flowers; and the lakes and fountains scintillating in the sunshine, must have presented to the young musician, fresh from his lodging in the crowded city, a vision of endless beauty. The very air of the place breathed a music of its own, as, laden with the perfumes of countless blossoms, it was wafted into the apartments set aside for his use. Hard work lay before him; but what work could be too hard when performed amidst such exquisite surroundings as these, and for a master whose unstinting generosity and fatherly care for those about him were so widely known? From the outset Haydn realised that here he would enjoy the freest scope for the exercise of his gifts, with the additional advantage, for which the greatest masters might well have envied him, of being able to give practical effect to whatever he wrote before committing it to the judgment of the world outside.

No wonder, then, that under such favouring conditions as these compositions poured from his pen; nor was it long ere the musicians whom he commanded had learnt to regard him with affection, and to vie with each other in their eagerness to fulfil his wishes.

In about a year from the date of Haydn’s engagement Prince Paul Anton died, and the event marked a further advancement in the composer’s fortunes. Prince Nicolaus, who succeeded his brother, was a passionate lover of the arts and sciences, in addition to being one of the most generous and warm-hearted of men. His succession implied an added magnificence and pomp to what seemed already perfect. To Haydn he gave an assurance of his good-will and appreciation by raising his salary from four hundred to six hundred florins, and, later, to seven hundred and eighty-two florins (or £78), allowed him to select additional musicians, and at the same time gave him to understand that he should look for an increase in the number of performances. The Prince himself played the baryton, or viola di bardone—a stringed instrument of sweet, resonant tone, which, like the viol da gamba, to which it bore some resemblance, has long since ceased to be heard. As the Prince prided himself on his playing, Haydn was required to produce endless pieces for the instrument, and he was even at considerable pains to acquire a knowledge of the baryton itself, thinking thereby to afford his master pleasure. To his chagrin, however, he discovered that his efforts in this direction were not at all appreciated by the royal performer, who had no fancy to see himself outskilled.

In 1766 Werner died, and Haydn succeeded to the full title. He had thus reached the summit of his boyish ambition, and could look back with pride to those early days when he studied the ‘Complete Chapel-master’ in his lonely garret, and longed for the day to come when his father’s dream might be realised. And what of the parents whom he had left behind in the little village? How had they fared during these long years of struggle and success? The mother died seven years before Haydn received his appointment to the Esterhazy family, and while he was still striving to make his way; and the pleasure which success had brought to him must have been tinged with the regret that she had not lived to witness it. Mathias had married again, but he managed to find his way to Eisenstadt, where, to his pride and joy, he heard Joseph addressed as ‘Herr Capellmeister!’ Thither, also, came Michael, who had been appointed director and concertmeister to Archbishop Sigismund of Salzburg, to spend several happy days with his elder brother.

Haydn’s fame as a composer had spread far beyond the walls of Eisenstadt. Musicians of Leipzig, Paris, Amsterdam, and even London, were playing his symphonies, trios, and quartets, whilst theWiener Diarium—the Austrian official gazette—for 1766 refers to him as ‘the favourite of our nation,’ and pays him the high compliment of comparing him with Gellert, the most esteemed poet of the day. ‘What Gellert is to poetry Haydn is to music,’ writes the critic.

Werner’s death was shortly followed by an event which implied a still greater change in Haydn’s surroundings. Prince Nicolaus had been engaged in carrying out a scheme for the rebuilding of his shooting-box near Süttör on a scale of magnificence rivalling that of Versailles in its palmiest days, and, the works being completed, the Prince moved thither with the major portion of his household. No more lonely spot or one more unhealthy in its natural state, could have been chosen than that which formed the site of the [128]new residence. Standing in the middle of a salt marsh, forming the southern extremity of the great lake called the Neusiedler-See, Esterház, as the palace was named, was quite cut off from the outside world. The work of draining and reclaiming the land, however, had effected such an improvement that what in its primitive condition had been little better than desolate swamp, resounding to the harsh cries of wild-fowl, was now become a scene of veritable enchantment. The thick wood which lay behind the house had been transformed into shady groves and open glades for deer, whilst the front windows of the palace looked upon extensive flower-gardens, with a profusion of hothouses, summerhouses, arbours, and temples. The castle itself comprised a hundred and sixty-two apartments, splendidly decorated, and filled with costly collections of art. Even Eisenstadt itself paled before the beauty and magnificence of this new palace of Aladdin which the genie of wealth had raised on the dismal marsh.

The provision for music and acting was on a scale as elaborate as that of the rest of the palace. A splendid theatre, designed and equipped for the performance of operas and dramatic works, had been reared near the castle, and beside this stood a smaller theatre, fitted up for the marionette performances, to the perfecting of which the Prince had devoted much attention. The orchestra was reinforced by travelling players of eminence, whilst, in addition to singers especially engaged from Italy, various strolling companies were invited to give their services from time to time. It was an essential part of the scheme that this body of musicians and actors—temporary as well as permanent—should form one family, with Haydn as its head; but the appellation of ‘Father Haydn,’ by which the Capellmeister was known to the members of his orchestra, had its origin in an affection which owed nothing to discipline or arrangement. ‘Friend, go back to the first allegro,’ was the wording of a direction written by Haydn on the cover of one of his confrère’s music-books, and it may be taken as an indication of the happy relations which existed between the chief of orchestra and his men.

A picture of the daily life at Esterház from spring to autumn would show a constant round of life in its fullest and gayest sense. Visitors poured in at its hospitable gates in an unbroken stream; and the strain upon those whose duty it was to provide amusement for the pleasure-seekers must have been enormous. If there was abundance of work, however, there was no lack of helpers, and thus Esterház became a little world in itself—a centre of music and acting, as well as an emporium of art treasures. Thither came the Empress Maria Theresa on a visit, and Haydn seized the opportunity of reminding her of the chastisement which she had ordered him to receive when, as a fair-haired chorister, he had clambered up the scaffolding-poles of the royal palace. ‘Ah, well!’ replied the Empress with a smile; ‘you must see yourself, my dear Haydn, that the whipping has produced good fruit!’

Prince Nicolaus, though an excellent master, and one for whom Haydn entertained a deep affection, was, nevertheless, somewhat unreasonable in expecting his Capelle to share his devotion to Esterház as an almost continuous residence. The visits to Vienna were getting fewer and shorter—even the winter at Eisenstadt had been reduced to its shortest limits—and, admitting the attractions of the new palace as a summer residence, the musicians were pining to see their wives and families, and to breathe once more the air of the city. In 1772 the stay at Esterház was prolonged so far into the autumn that the musicians became impatient. The Prince had made no announcement of the date of his departure, and Haydn at length resolved to convey to his royal master a delicate hint of the orchestra’s desire to be set free. He therefore announced the performance of what he called ‘The Farewell Symphony’; and when the evening arrived, sixteen performers took their seats in the orchestra to carry out the Capellmeister’s scheme, whilst the Prince, having no suspicion of what was intended, occupied his accustomed place. All went as usual until the last movement was reached, when one pair of performers rose from their chairs, extinguished their candles, and quietly left the orchestra. The music proceeded, and a little later a second pair arose, went through the same pantomime, and disappeared, the Prince watching their movements with a puzzled expression that almost destroyed the gravity of the rest of the performers. Pair after pair thus left the building, until at last only Tomasini (the Prince’s favourite violinist) and Haydn remained. Finally, Tomasini blew out his candle, bowed to the Prince, and retreated, and as Haydn prepared to follow his example, the Prince’s eyes were opened to their drift. Good-humouredly regarding the whole thing in the light of a joke, he exclaimed, ‘If all go, we may as well go too!’ and immediately quitting the theatre, he gave directions for the departure of the household.

We must pass over the years which intervened between the date of the ‘Farewell Symphony’ (the merits of which as a musical work must not be confused with the circumstances under which it was written), and the year 1790, when, to his great grief, Haydn lost the master to whom he had become so deeply attached. The Prince left Haydn a pension of one thousand florins, on condition that he retained his post as Capellmeister to the family. Prince Anton, however, who succeeded his brother, had no taste for music. The Capelle was practically disbanded, and though Haydn kept his official position, his constant presence at the palace was no longer necessary, and he took up his residence in Vienna.

Some three years before this event several attempts had been made by English musicians of eminence to induce him to come to London and play at the professional concerts, but he had resisted these offers with one and the same excuse—he could not leave the master whom he loved. On the last occasion Salomon, the well-known musician and concert-director, had dispatched a publisher named Bland to Esterház to endeavour to persuade Haydn to alter his mind. Bland was shown into a room adjoining that in which Haydn happened to be shaving, and whilst seated there he overheard the composer growling to himself over the bluntness of his razors. At length Bland caught the exclamation, ‘Ach! I would give my best quartet for a good razor!’ and without more ado, he rushed off to his lodgings and returned in a few minutes with a pair of razors, which he presented to Haydn. The Capellmeister accepted the gift with a smile, and rewarded the enterprising publisher with a copy of his latest quartet, which, later on, was produced in London, and has ever since been known by the title of the ‘Rasirmesser’ (Razor) quartet.

The death of Prince Nicolaus removed the only obstacle to Haydn’s undertaking a journey to London; consequently, when one morning he found a visitor awaiting him at his house, who announced his business thus: ‘My name is Salomon; I have come from London to fetch you; we will settle terms to-morrow,’ Haydn regarded the matter as practically settled.

Mozart was in Vienna at the date of Salomon’s visit. Haydn had been strongly drawn towards the young musician ever since the time, five years before, when, after listening to one of Mozart’s quartets, he had delighted the heart of Leopold Mozart by declaring that his son was the greatest composer he had ever heard. Mozart’s affection for Haydn was equally warm, and now, on hearing that the latter contemplated a journey to England, he tried to persuade him against it, urging that he was advanced in years and unacquainted with the English language. Haydn listened to his friend’s objections, and then observed with a smile, ‘No matter; I speak a language which is understood all over the world.’ ‘Then,’ said Mozart, grasping Haydn’s hand as he spoke, it is good-bye, for we shall never meet again!’ The words were prophetic, for only a year later Haydn in London was stunned by the news of Mozart’s death.

It was a stormy December day when Haydn and Salomon set sail from Calais, and the passage to Dover was a long and trying one for the travellers. Nevertheless, Haydn, taking his stand on the deck, enjoyed his first sight of the waves, and as the spray dashed in his face he recalled with a smile how he had attempted to write the tempest music for the actor-manager Kurz. A long interval separated him from those days of keen want and fierce struggle, when he strove, almost against hope, to establish a foothold for himself in the music-loving city of Vienna! Now he was travelling to a greater city, not as an unknown, struggling student, but with the assurance of a welcome befitting one whom fame had already claimed for her own.

The night of his arrival in London was passed at Bland’s music warehouse, No. 45, High Holborn but [133]the following day he went to live with Salomon at the latter’s lodgings, No. 18, Great Pulteney Street, Golden Square.[9] Salomon had by no means overestimated the warmth of the welcome which London was prepared to give to the composer whose works were already familiar to English music-lovers. From every quarter admiration and attentions were lavished upon him; all the most celebrated people besought his acquaintance, and he was invited everywhere. Yet his equanimity never deserted him. He took everything very simply, and as if it were his due, and thoroughly enjoyed the [134]river parties and picnics which were arranged in his honour. Not so, however, the lengthy dinners or evening entertainments in town, where his ignorance of the language and customs of his hosts made him feel less at his ease. The incessant noise of the streets was a source of great discomfort to one who had been so long accustomed to the silence of the country; and he positively refused to fashion himself to the late hours of London. When, later on, he removed his lodging to Lisson Grove, he writes in a strain of rejoicing to a Vienna friend that he has at length found himself in the country amid lovely scenery, where he lives as if he were in a monastery! It is difficult for us to imagine the Lisson Grove of a century ago, when the road stretched away through green fields and woodland spaces.

The first of Salomon’s concerts was held on March 11, 1791, at the Hanover Square Rooms. The hall was crowded, and the performance of Haydn’s ‘Symphony’ (Salomon, No. 2) was received with great applause; nor would the audience remain satisfied until the adagio movement had been repeated—an event of such rare occurrence in those days as to call for comment in the newspapers. This marked the beginning of a most successful series of concerts, at each of which Haydn received a great ovation. His benefit took place on May 16, and realized £350.

The Handel Commemoration Festival—the fifth and last of the century—was held in Westminster Abbey during this visit, and it must have been a moving sight to Haydn to observe the crowds flocking to the Abbey early on that summer morning in order to hear the master’s greatest work. Haydn had secured a seat close to the King’s box—a position which commanded a view of the nave and the vast concourse of listeners. Rarely had those venerable walls looked down upon such a sea of expectant faces as that which was turned towards the distant bank of musicians and singers when the moment drew nigh for the performance to begin. There was reverence expressed in the hushed silence which pervaded every nook and corner of the Abbey at that supreme moment—a befitting reverence both for the dead composer whose immortal work was to be celebrated, and for the sacredness of the subject which he had chosen for illustration. As the oratorio proceeded Haydn became more and more impressed. He had never heard the ‘Messiah’ performed on so grand a scale before, and when the opening chords of the ‘Hallelujah Chorus’ rang through the nave and the entire audience sprang to their feet, he burst into tears, exclaiming to those around him, ‘He is the master of us all!’

The first week in July found him at Oxford, at Commemoration, whither he had gone to receive the honorary degree of Doctor of Music. Three grand concerts were given in his honour, the principal singers and performers having been brought from London, and on each occasion his compositions were greeted with great applause. He appeared at the third concert clad in his Doctor’s gown, and met with an enthusiastic reception. It was evident, however, that he was not feeling quite at home in his new vestment, for when the students clapped their hands and shouted he raised the gown as high as he could, exclaiming as he did so, ‘I thank you,’ whereupon the applause was redoubled. Haydn writes to a friend that he had to walk about for three whole days clad in this guise, and he only wishes that his Vienna friends could have seen him.

Amidst the wealth of incident which signalised his visit two little scenes found a cherished corner in Haydn’s memory. He was invited by the Prince of Wales to visit Oatlands Park as the guest of the Duke of York, who was spending his honeymoon there with his young bride, the Princess of Prussia. The seventeen-year-old bride welcomed the sight of Haydn’s kindly face and the familiar sound of the German tongue, and in one of his letters he describes how the liebe Kleine sat beside him as he played his ‘Symphony,’ humming the well-known airs to herself, and urging him to go on playing until long past midnight. The Princess also sang and played to him, whilst the Prince of Wales played the violoncello, their attention being entirely given to Haydn’s works. It was during this visit that the portrait by Hoppner was painted, which hangs in the gallery at Hampton Court.

The second picture, though one of a very different kind, he himself described as having afforded him one of the greatest pleasures of his visit. He went to St. Paul’s to witness the gathering of the charity children at their anniversary meeting, and the sight of the children’s faces and the sound of their young voices echoing through the vast building touched him deeply, and no doubt recalled to his mind the singing of the choristers in St. Stephen’s Cathedral in bygone days.

Frau Haydn had evidently heard reports of her husband’s successes, for she troubled him with a letter at this time, in which she related how she had found a small house and garden in the suburbs of Vienna, which she felt would exactly suit her requirements when she became a widow. She therefore begged that he would send her the money—a matter of two thousand gulden—to complete the purchase. Haydn did not comply with this simple request, but on his return journey to Vienna he inspected the house, approved it, and bought it for himself!